Dr. Davydova

Research Fellow, Arctic Research Center,

Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Russian Academy of Sciences

The Chuvans. Spiritual culture (mythological worldview, traditional beliefs, holidays and rituals)

Both spiritual and material Chuvan culture constitutes a complex mosaic of Yukaghir, Koryak, Russian, Chukchi, and Even elements. It is hard to identify something specifically Chuvan in this combination, yet, Chuvan culture stands out because of its eclectic nature.

Despite the powerful influence of Orthodox Christianity, Chuvans preserved many pagan notions and rituals. Like most peoples of the Far North, Chuvans have traditionally been animists believing in spirits and all elements of nature having a soul. Along with practicing Orthodox Christianity, Chuvans worshipped master spirits of the earth, forest, rivers, and animals.

The earth was perceived as a certain divine principle where scolding, stabbing, cutting, and digging was prohibited. Nikolay L. Gondatti wrote that the Markovo Chuvans worshipped the god Apy (grandfather) who lives in the earth, “he looks like a human being, like his wife, but he is covered with fur all over; he is always dressed in clean clothes that he changes often, and he likes everything to be clean.”

Prayer on the river Markovka before the spawning run, 1897–1907.

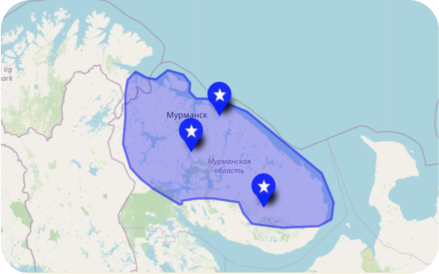

Both settled and nomadic Chuvans practiced thanksgiving rituals devoted to luminaries, various natural objects, spirits of animals killed during hunting. Offerings were given to spirits. In spring, entire Chuvan families offered gifts to the river, their benefactress. The annual rite of giving gifts to the river has retained its sacred nature even today. Old trees were given ribbons, pieces of cloth, and money. Like many peoples, Chuvans believe in the magic attributes of fire and performed “fire” rituals.

People looking for something specifically Chuvan remembered that old men spoke of “grass people living in the tundra” or “grass people are a Chuvan thing, the Chukchi had nothing of the sort. In Kanchalan, for instance, you will no longer meet grass people.” Tatiana Shentalinskaya studied the folklore of Markovo Chuvans and recorded stories of meeting and fighting “grass people.” In her opinion, these stories may have come from Chuvans’ encounters with wooden idols dressed in clothes of ritual grass. These idols belonged to Koryak clans from the village of Paren. Oral histories have it that the villages of Yeropol and Chuvanskoye used to have four large wooden idols standing along the village perimeter “looking onto the four directions of the compass.”

There were also hunting and fishing rituals. Chuvans held a cleansing ritual before going on the spring moose or reindeer hunt. Hunters went through an arch made of two trees with a crossbeam hung with animal pelts, decorated with ornaments, multicolored pieces of cloth, ribbons, etc. Then, people made sacrifices to the masters of the earth, river, and forest. A boy’s first kill in a hunt was marked by a special ritual. First, an “old woman” drove the young hunter away, and only then the community held a celebration. A celebration marked killing a bear in a hunt, too: the entire village got together and ate the bear at once. After that, the bear’s boiled head was taken to the tundra. Some Chuvan groups had a taboo on killing swans. They believed that if a swan was killed, a family member could fall ill or die.

A special role was assigned to shamans. They treated the sick, exorcised evil spirits, engaged in divinations, and predicted the weather. The shamans beat their drums and skillfully imitated the sounds of animals and birds.

Ritual cap with tassel.

Settled Chuvans’ funeral rites followed the Orthodox Christian customs. Chuvans performed at the cemetery, but they also featured pre-Christian elements. Prior to the 1940s, the deceased were buried without a coffin; coffins came into use after the appearance of collective farms. They put cigarettes or tobacco in men’s coffins, and sewing implements were put in women’s coffins. Chuvans made sure that funeral clothes did not have metal things such as pins, buttons, or ornaments. A wake was held after the funeral, and people drank in honor of the deceased. Nomadic Chuvans were buried in shallow graves lightly covered with soil and leaves. Chuvans believed the dead to be reincarnated in newborns, and when they gave a newborn a name, they did so as part of a special ritual. They held a stone and called out the names of the deceased one by one. If the stone moved when a name was uttered, it meant that its bearer had returned, and the child was given their name.

Settled Chuvans celebrated marriages following the Russian custom, with a church wedding. Before the wedding, the bride held a bachelorette party in her home, and the bridegroom held a stag party in his home. There were songs performed at weddings to the accompaniment of homemade accordions, balalaikas, and fiddles.

Settled Chuvans had their children baptized in churches, nomadic Chuvans gave their newborns a reindeer with a special brand; amulets were sewn on the child’s clothes to protect the infant from evil spirits and diseases.

Settled Chuvans’ calendar rites include the “welcoming the sun” celebration marking the coming of spring (the start of a new annual cycle). As the sun rose, Chuvans held dog sled races and then assembled at the largest house, danced, and sang. Another celebration, the so-called “first water” celebration marked the ice melting in spring as a symbol of life reviving after the long winter. Nomadic Chuvans’ celebrations were connected with the reindeer herding cycle and involved sacrificing dogs and reindeer. Playing drums collectively was a required ceremony at celebrations.

Along with their traditional holidays, Chuvans also celebrate such holidays as Christmas, Yuletide, Shrovetide, Easter, and Pentecost. For Christmas, everyone always goes to the river to draw water from an ice-hole. Water drawn on that night is believed to be holy. Yuletide is marked with mummery and caroling, and dog-sled riding marks Shrovetide. Chuvans make

kuliches

(Easter cakes) and decorate eggs for Easter, and also throw flower wreathes in the water on Pentecost.

Cathedral of the Life-Giving Trinity, Anadyr, 2023.

Today, Chuvans are Orthodox Christians, but they did preserve some traits of their pre-Christian rituals. In the last decades, Protestantism, and particularly the Baptist denomination have also gained traction.