|

|

Valentin Gusev

Senior Research Fellow

Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences

|

Nganasan

I. Sociolinguistic data

1. Existing alternative names

Once they used to call the language Tawgi or Tawgi-Samoyed (Tawgisch in German). Sometimes, its name was based on the self-definition of Nganasan

язык (народа) ня

[language of the peoples Nya].

The self-designation of the Nganasan speakers is

няа.

Today, the ethnonym Nganasans is commonly accepted, but earlier, it was Tawgi.

2. General characteristics

2.1.

Total number of speakers and their ethnic group

In the 2020 Census, 300 people indicated their command of the Nganasan language. But it is highly unlikely that the actual number of people that are fully proficient in it exceeds 20-30.

Total Nganasan population (based on the 2020 Census) is 693 people.

2.2.

Age structure of native speakers

All fully proficient Nganasan speakers are aged over 60. Some of young Nganasans are passive speakers or have limited command of the language.

Nganasans can be divided into three age groups, and each one of them corresponds to a certain level of language proficiency:

-

Born between 1920s and 1930s. This generation never went to school, the Nganasan language is fully native for them and remains their main tool of communication. These people are passive Russian speakers, they usually speak it well but with a strong accent (at least when it comes to traditional subjects). Today, there are only few representatives of this generation left. They have virtually no possibility of communicating with each other, since they often live in different settlements and even when it is not the case, they have considerable difficulty moving.

-

Born in the 1940s. This is the first generation that went through school or boarding school. As a rule, they started school speaking no Russian whatsoever, but learned the language during their studies (often as a result of fairly brutal methods of teaching). After graduating from secondary school, they went back to tundra to live with older generations. Representatives of this group are usually fully fluent in both Russian and Nganasan (language, as well as traditional culture). They speak Nganasan between themselves and with the older generation, and Russian with the younger one. But as their peers and older people pass away, Nganasan plays less and less of a role in their lives and is gradually replaced by Russian.

-

Younger generation. As a rule, their main communication language is Russian. Their proficiency in Nganasan is overall proportional to their age, ranging from a rather fluent everyday language among 50- and 60-year-olds to a complete lack of any linguistic knowledge among most of the young people. The data provided by V. Krivonogov show that there was a sharp decline in language transmission to the generation of the 1960s, the trend that grew even stronger in the 1970s.

It goes without saying that the level of proficiency of each particular person depends on his/her personal life story. Today, even some 20- and 30-year-olds are quite fluent in everyday Nganasan owing to their dealings with older generations, but their main language of communication is undoubtedly Russian.

2.3. Sociolinguistic characteristics

2.2.2. Extinction threat

The language is on the

brink of extinction

(critically endangered, nearly extinct).

20-30 native speakers, all of them aged.

As for the language situation in separate settlements, until recently, Nganasan was particularly well preserved in Volochanka and Ust-Avam. This is where most of the older speakers lived. In Novaya and other settlements of the eastern part of Taimyr, some Nganasans switched to the Dolgan language due to the predominance of Dolgans. There were only young Nganasans living in Dudinka and other cities. Over the last few years, the situation has changed: many aged Nganasans moved to Dudinka, which has further reduced the use of the Nganasan language in rural settlements. At the same time, Nganasan speakers in Dudinka are not numerous enough to change the overall language situation.

2.2.3. Use in various spheres

|

Sphere

|

Use

|

Comments

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

yes

|

To a small degree, older and middle generations, along with Russian; communication between peers (but since there are few of them left, it does not happen often)

|

|

Education: nursery school

|

course

|

|

|

Education: school

|

course

|

In primary school

|

|

Education: higher education

|

no

|

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

course

|

For children

|

|

Media: press (incl. online editions)

|

yes

|

Monthly publication (1 page) in the Taimyr newspaper

|

|

Media: radio

|

yes

|

Daily radio broadcast

|

|

Media: TV

|

yes

|

Weekly TV program

|

|

Culture (incl. live folklore)

|

no

|

With the breakdown of the language community and the demise of most of the storytellers and listeners, the tradition of folklore performances has virtually ceased.

|

|

Fiction in native language

|

few

|

Sometimes, there are translations of poems or small prose works from Russian into Nganasan that are used either for language courses, or for the Nganasan newspaper page.

|

|

Religion (use in religious practice)

|

no

|

With the demise of last shamans, the ritual practice and consequently the use of Nganasan in it has ceased. The Christian church, a place of worship for some of Nganasans, does not use the Nganasan language.

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Justice system

|

no

|

|

|

Agriculture (incl. hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

no

|

Nganasans lost their skills of traditional reindeer herding in the late 1970s. Hunting and fishing concern mainly young people who speak no or poor Nganasan.

|

|

Internet (communication/ existence of websites in native language, not media)

|

few

|

There are Nganasan groups in chat rooms and on social networks, and sometimes they use Nganasan words or phrases in their communication.

|

The Nganasan language is used in the communication between older generations (born in the 1940s or earlier). Younger generations speak Russian among themselves, as well as with older generations. Consequently, Russian starts to prevail over Nganasan more and more over the time.

It is used to be the main language of communication in the Nganasan traditional activity — reindeer herding – while it existed (until the late 1980s) and even some time afterwards, as long as some of Nganasan families stayed in their regular spots in tundra, thus preserving a semi-traditional way of life (wild deer hunting and fishing). Nowadays, older people moved into settlements and were replaced by a younger generation that speaks Russian. There are no other official, economic or information spheres, in which the Nganasan language is still used.

As for education, there are no courses taught in Nganasan. In villages, there are language courses in primary and secondary schools, but they are very limited. In Dudinka, there are special courses designed to prepare native (Nganasan) school teachers. There are Nganasan schoolbooks and teaching aids for primary school. There is also the

Школьный нганасанско-русский и русско-нганасанский словарь

[School Nganasan-Russian and Russian-Nganasan Dictionary], as well as a Russian-Nganasan phrasebook.

There is no original scientific or fiction literature in this language. A few collections of folklore texts were published over the years.

The Nganasan language was used in the traditional shamanic practices as long as they existed (until the late 1980s). At present, Nganasan is not used for any rituals of worship or religious education (for any religion whatsoever). There is a fragment of the Gospel of Luke that was translated in Nganasan.

A Nganasan page in the Taimyr newspaper is published monthly, on the average. A 30-minute time slot for broadcasts in indigenous languages is allotted daily by the Taimyr radio station. This time slot is divided between four local languages (Nganasan, Enets, Nenets, and Dolgan). At the same time, the villages inhabited by the majority of Nganasan (and Nganasan-speaking) population do not pick up local radio broadcasts.

Nganasan is used in the performances of folklore groups that take place regularly in Dudinka, and also sometimes in other Russian cities or abroad. However, these events are destined to showcase the Nganasan traditions to the outside audience that does not speak the language, therefore, Nganasan doesn’t perform any communicative function.

2.4.

Information about written language and its existence

To record Nganasan, researchers used at first Latin, then Cyrillic orthography based on the Nenets script that was adapted to Nganasan. The alphabet tailored to the Nganasan language was elaborated by N. Tereschenko and published in 1986, although she did use it even earlier for her own research. The first official version was approved in 1990; its new version, with several symbols replaced and added, was accepted in 1995.

Аа Бб Вв Гг Дд Ее Ёё Жж Зз Ǯǯ Ии Йй ” Кк Лл Мм Нн Ӈӈ Оо Өө Пп Рр Сс Çç Тт Уу Υү Фф Хх Цц Чч Шш Щщ Ъ Ы Ь Ээ Әә Юю Яя

The letter i can be added to these letters for a better rendering of combinations of hard consonants

т, д, н

with a vowel

и

(see Phonetics); the distinction between hard and soft consonants before

и

and

ү

, which can help differentiate, for example, different forms of nouns:

быныни

(‘our ropes’ in nominative or accusative case) vs.

быныні

(‘our ropes’ in genitive case).

The script is used for school books and training aids, collections of folklore, as well as the monthly newspaper page.

The Avam dialect was used as a base for teaching aid and printed materials. There is virtually no standardization or fixed functional styles.

3. Geographic Charasteristics

3.1.

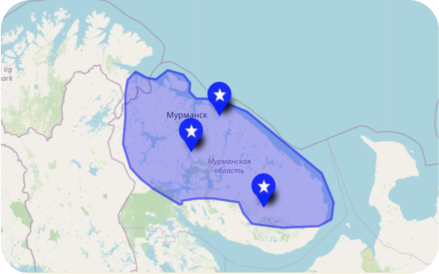

Subjects of the Russian Federation with compact residence of native speakers

The traditional Nganasan territory is situated on the Taimyr Peninsula, from the boundary between forest-tundra and tundra in the south to the Byrranga Mountains in the north. Families with their herds of domestic reindeer followed the migrations of wild reindeer northward (in spring) and southward (in autumn), leading herds into forest “for winter”.

After the death of domestic reindeer in the late 1970s, Nganasans settled mainly in three villages of the current Taimyr Dolgano-Nenets Municipal District, Krasnoyarsk Krai: Ust-Avam, Volochanka, and Novaya. In time, numerous Nganasans moved to the nearest cities: Dudinka and Norilsk.

3.2.

Total number of localities

traditionally inhabited by native speakers

Traditionally, Nganasans were nomads. The traditional nomadic routes of Nganasans lie from the northern boundary of the forest-tundra to the Byrranga Mountains ridge. There have been reliable recordings of the presence of Nganasans in Taimyr since the second half of the 18

th

century. Since the 17

th

century, there were several tribal, possibly generic names recorded in Taimyr that probably belonged to Nganasans. There is no documentary evidence regarding an earlier period.

Today, Nganasans are mostly concentrated in Taimyr settlements. According to the 1992-1994 data by V. Krivonogov, they were distributed as follows: Volochanka (392 people, 43% of total population), Ust-Avam (295 people, 33%), Novaya (83 people, 9%), and Dudinka (64 people, 7%), as well as several people in other settlements of the Taimyr Peninsula, Norilsk and its suburbs. In Volochanka, Ust-Avam, and Novaya, Nganasans live together with Dolgans, and the later significantly prevail in Novaya. In Dudinka, Russians constitute the majority. In total, there were 820 Nganasans in 1992—1994. The 2020 Census indicates 862 people.

4. Historical Dynamics

The number of native speakers and corresponding ethnic group based on various censuses (starting from 1897) and other sources.

|

Census Year

|

Number of Native Speakers (men)

|

Size of Ethnic Group (men)

|

Comments

|

|

1897

|

1326

|

—

|

Nganasans and Enets were counted together, one might assume that Nganasans account for approximately half of this number.

|

|

1926

|

—

|

—

|

Nganasans were probably included into Samoyeds together with Enets and Nenets.

|

|

1937

|

|

|

|

|

1939

|

|

|

|

|

1959

|

701

|

750

|

|

|

1970

|

719

|

953

|

|

|

1979

|

790

|

867

|

Native speakers include the respondents that indicated another language as their main one (for example, Russian).

|

|

1989

|

1096

|

1278

|

Native speakers include the respondents that indicated another language as their main one (for example, Russian).

|

|

2002

|

505

|

834

|

|

|

2010

|

125

|

862

|

The number includes all the respondents who indicated their command of the language, regardless of their level of proficiency; it is quite likely that the number of fully proficient speakers is much lower.

|

|

2020

|

300

|

693

|

|

II. Linguistic Data

1. Position in the genealogical classification of world languages

Nganasan belongs to the Samoyedic branch of the Uralic language family. Within the Samoyedic group, it is traditionally included in the North Samoyedic subgroup together with Enets and Nenets. Although there is an alternative point of view that Nganasan is a separate branch within the Samoyedic languages. Until the middle of the 20

th

century, it was often considered as a dialect of the Nenets language.

2. Dialects

There are two main dialects: Avam (west and center of the Taimyr Peninsula) and Vadeyev (east of the Taimyr Peninsula). They are very close and mutually intelligible. There are some slight differences in vocabulary, phonetics, probably grammar (these differences have not been fully analyzed yet). The Avam dialect consists of two sub-dialects: Avam itself, whose native speakers traditionally roamed in the west of Taimyr, and Taimyr spoken by the inhabitants of the centre of the peninsula. Today, the varieties of the Nganasan language are associated with villages Ust-Avam (Avam sub-dialect), Volochanka (Taimyr sub-dialect), Novaya (Vadeyev sub-dialect), although their native speakers often move from one settlement to another.