Tundra Nenets language

The former designations of Tundra Nenets include Yurak Samoyed, Yurak, and Samoyed. The name Yurak Samoyed used to include both languages: Tundra Nenets and Forest Nenets. Today, Tundra Nenets and Forest Nenets are regarded as independent languages and no longer dialects of the same language. The self-designations of the Tundra Nenets language are ненэй вада, ненэця’ вада (Nenets language).

-

General Сharacteristics

2.1. TThe Number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group

The population of Nenets (based on the 2020 Census) is 49.787 men. Respondents who indicated Tundra Nenets as their native language (based on the 2020 Census): 36.417 men. Respondents who indicated their proficiency in Tundra Nenets (based on the 2020 Census): 23 506 men. In some traditional localities (for instance, Gyda and Antipayuta of the Tazovsky District and Nori of the Nadymsky District, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug), the command of Tundra Nenets was next to nil, based on the 2010 Census, although it was indicated as a native language by the majority of inhabitants. Thus, it means that the respondents or census takers did not necessarily indicate their native language as the one they were fluent in.

2.2. Age of Speakers

In the Nenets Autonomous Okrug (NAO), only the middle and older generations are proficient in Tundra Nenets. In the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (YNAO), all generations, on the whole, speak Tundra Nenets. In the Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenets District (TDND) of Krasnoyarsk Krai, the younger generation is less proficient and fluent in Tundra Nenets than older speakers.

2.3. Sociolinguistic Characteristics of Tundra Nenets

In NAO, Tundra Nenets is under the threat of extinction (definitely endangered), except for the area occupied by the Yamb-To community. In both YNAO and TDND of Krasnoyarsk Krai, Tundra Nenets is considered vulnerable and potentially endangered, and the process of language shift is underway.

Compared to other languages of indigenous peoples of the North, Tundra Nenets is relatively well-preserved. However, its vitality level varies greatly and depends on the region: it is distinctly endangered in the west, in NAO, and particularly well-preserved in the northeastern part of its language area (in particular, in YNAO).

Based on the data for 2010 provided by S. Burkova in the article about Tundra Nenets, encyclopedia Yazyk I Obshestvo (Language and Society, 2016), there were 48% of Tundra Nenets fluent in their native language in the Republic of Komi, approximately 55% in YNAO, 46% in TDND of Krasnoyarsk Krai. Burkova pointed out that “the relatively high degree of preservation compared to other regions can be explained by the remoteness of the areas inhabited by Tundra Nenets from large settlements, the compact way of life of the ethnic group, and the maintenance of its traditional economic activity – large-scale reindeer herding”. It should be pointed out that that the shift herding, when children and women often remain “on the base” (i.e. in a fixed settlement), instead of an encampment in the tundra, contributes to the loss of Tundra Nenets. Whereas the traditional way of reindeer herding prevalent in Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug and Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai – when the entire family permanently lives in a nomad camp, except for school-age children who stay at boarding schools during school year and come back to tundra only for vacations – helps to preserve Tundra Nenets.

Although Tundra Nenets is relatively well-preserved, the population of native speakers has been steadily declining since the language is used less and less in family communication and the natural tradition of language transmission from parents to children has been compromised. Thus, S. Burkova pointed out that “although the results of sociolinguistic surveys show that the attitude of Tundra Nenets towards their ethnic language is positive, in reality, the majority of parents prefer to speak Russian with their children, for they consider it to be more important, the key to education and professional career. It is also affected by the deep-rooted notion that one cannot be fluent in a majority language with a more powerful functionality unless he/she gives up the native language.”

2.3.2

. Use in Various Fields

|

Sphere

|

Use

|

Comments

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

yes

|

|

|

Education: nursery school

|

subject and tool

|

|

|

Education: school

|

subject and tool

|

|

|

Education: higher education

|

subject

|

Institute of Peoples of the North, Herzen State Pedagogical University(3–8 school hours/week)

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

subject and tool

|

|

|

Media: press (incl. online editions)

|

yes

|

|

|

Media: radio

|

yes

|

|

|

Media: TV

|

yes

|

|

|

Culture (incl. live folklore)

|

yes

|

|

|

Fiction in native language

|

yes

|

|

|

Religion (use in religious practice)

|

yes

|

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Justice system

|

yes

|

|

|

Agriculture (incl. hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

yes

|

|

|

Internet (communication/ existence of websites in native language, not media)

|

yes

|

|

Tundra Nenets is quite widely used in intra-family communication, but mainly in mono-ethnic entities; mixed families tend to choose Russian as their language of communication.

The use of Tundra Nenets in education is linked to the name of Father Irinarkh (whose mundane name was I. Shemanovsky), head of the Obdorsk mission of the Russian Orthodox Church, who opened a boarding school for non-Russian children in Obdorsk in 1889 (nowadays, Salekhard). During the first year of school, students were taught in their native (Tundra Nenets) language; the second year, there were two languages of instruction; whereas the third year was taught entirely in Russian. Starting from 1932, children of Nenets Autonomous Okrug were taught in their native (Tundra Nenets) language in 5 national schools, then, several years later, already in 15. In 1935, there were 5 primary schools in YNAO, where children were taught in Tundra Nenets. By the late 1930s, approximately 96% of Tundra Nenets children in primary schools were taught in their native language. Subsequently, Tundra Nenets has been gradually replaced by Russian as the language of instruction. In the school year 1980–1981, only 799 primary school children had lessons in their native (Tundra Nenets) language. In 1986–1987, there were only 249, and in the subsequent years, the teaching in Tundra Nenets had virtually ceased to exist.

Nowadays, Tundra Nenets is rarely used as the language of instruction, only as an auxiliary means in preparatory and first classes whenever there are children with poor Russian or no Russian at all. It is mainly taught from 1st to 9th grades. Class hours per week in primary school amount to 1–4 hours, in secondary school ― 1–3 hours.

In printed media, Tundra Nenets has been used since 1932. At present, there are 7 periodicals that print articles in Tundra Nenets with varying degrees of regularity. In the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, there is a Nenets weekly supplement Ялумд (Dawn) to the Няръяна вындер newspaper (Red Tundra-Dweller). Since 2007, the ethnocultural center of the Nenets Autonomous Okrug publishes Пунушка, a bi-annual children’s magazine, which is mainly in Russian, but features some small texts (poems, songs, riddles) in Tundra Nenets. Since 2008, there exists Выӊгы вада (Word of Tundra), a journal published 4 times a year that features the Timeless Values section containing materials in Tundra Nenets (proverbs, poems, songs, riddles). The Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug has the only weekly newspaper that is entirely in Nenets, Няръяна Ӊэрм. Some articles in Tundra Nenets are also published once or twice a month in Советское Заполярье, a newspaper of the Tazovsky District, and once a month in Время Ямала, a newspaper of the Yamalsky District. In the Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, the Таймыр newspaper publishes articles in Tundra Nenets 3–4 times a week.

Radio broadcasting. In the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the Sever broadcasting company is responsible for radio broadcasting in Tundra Nenets: there is a weekly radio program Аргиш (broadcast time: 12 minutes). In the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the Ямал-Регион broadcasting company has two radio programs: a news program Ямал юн (Yamal News) (weekly broadcasts, broadcast time: 1 hour) and Недарма (Ancient Road) (weekly broadcasts, broadcast time: 1 hour). In the Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, the Таймыр broadcasting company has two radio programs broadcasting news in Tundra Nenets once a week (broadcast time: 30 minutes).

Television. In the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, the Sever broadcasting company is responsible for TV broadcasting in Tundra Nenets: there is a weekly TV-program Novosti Severa (broadcast time: 30 minutes). In the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, there is a TV news program Ялэмдад нумгы (Morning Star) broadcast twice a week (broadcast time: 30 minutes); Студия-Факт, the district broadcasting company of the Tazovsky District broadcasts a news program Тасу ява (Tazovsky Land) twice a week (broadcast time: 30 minutes). In the Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, the Таймыр broadcasting company has two TV programs presenting news in Tundra Nenets once a week (broadcast time: 10 minutes).

Tundra Nenets is also used in theater and cinema. A. Lapsui made a series of documentaries and feature films in Tundra Nenets: V Obraze Olenya po Nebosklonu (1993), Sem’ Pesen iz Tundry (2000), Praroditel’nitsi Zhyzni (2002), Nevesta Sed’movo Neba (2004), Nedarma (2007), Pudana ― Poslednyaya v Rodu (2010), etc. In 2012, the Nenets broadcasting company (Naryan-Mar) made Тюнтава (Nenets wedding), a short film in Nenets based on the traditional Nenets ritual and a play by P. Yavtysy. In 2014, there was released Белый ягель, a feature film in Tundra Nenets made by the director V. Tumayev and based on the works of Nenets writer A. Nerkagi. In 2012, the Lukomorie Pictures studio (Yekaterinburg) released a short animated film U Lukomoria that was produced in several languages of the Russian Federation, including Tundra Nenets. In 2013, the DCfilm Production Center (Moscow) released the animated film Kukushka in Tundra Nenets. Since 1996, the amateur dramatic group Илебц has been operating in the Social and cultural district center (Naryan-Mar) of the Nenets Autonomous Okrug. It prepares theatrical performances based on Nenets folklore in both Russian and Tundra Nenets. Tundra Nenets is also actively used in school plays in NAO, YNAO, and TDND of Krasnoyarsk Krai. Plus, these regions have numerous folklore groups that sing songs in Tundra Nenets.

Over the last decade, there were publications of Christian religious literature in Tundra Nenets. The Institute for Bible Translation published Rasskazy ob Iisuse Khriste (Stories about Jesus Christ, 2003), Yevangeliye ot Luki (Gospel of Luke, 2004), a fragment of Yevangeliye ot Ioanna (Gospel of John, 2008), and Yevangeliye ot Marka (Gospel of Mark, 2010). The missions of Vestnik Mira and Voskresenie together published the book of sermons by V. Bush Иисус ― маня илма (Jesus is our destiny, 1997), a Christian novel Хобцо (A find, 2012), and a collection of Christian stories Ири’ книга (The book of granddad, 2012). Tundra Nenets is also used in traditional religious practices during ritual acts: prayers to the supreme deity and sacrifices, as well as shamanistic rituals.

Over the last few years, a series of official documents were translated into Tundra Nenets and published. These included the Constitution of the RF, the Land Code, the federal law “About territories of traditional nature management of Indigenous ethnic minorities of the North, Siberia, and the Far East of the Russian Federation”, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Convention on the Rights of the Child, etc. In 2014, the anthem of the Nenets Autonomous Okrug was performed in Tundra Nenets for the first time. However, the use of Tundra Nenets by regional authorities and local governments on the whole is very limited, mostly it does not go beyond oral communication in the administrations of remote towns of the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug and the Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai.

In traditional economic activities, such as reindeer herding, hunting, and fishing, Tundra Nenets is used quite widely, but only in oral communication.

2.4.

Literature

The first known written text in Nenets is the translation of the Lord’s Prayer into Tundra Nenets in Severnaya i Vostochnaya Tartariya (North and East Tartary) by Nicolaas Witsen (Amsterdam, 1692). In 1787, the text of the Nenets fairy tale Вада-Хасово was published by Johann Vater in the journal Noviye Ezhemesyachniye Sochineniya (St. Petersburg). The first volume of Sravnitel’niye Slovari Vseh Yasykov i Narechiy (Comparative Dictionaries of All Languages and Dialects, 1789) by P. Pallas featured lists of words in Tundra Nenets. In 1831, Archimandrite Veniamin (his mundane name was V. Smirnov), head of the Orthodox mission destined to evangelize Nenets of the Arkhangelsk Province, translated the Gospel and several books of the New Testament into Tundra Nenets. In 1895, Y. Simbirtsev published Bukvar’ dlya Samoyedov, Zhivushih v Arkhangel’skoy Gubernii (ABC for Samoyeds living in Arkhangelsk Province) in Arkhangelsk. In 1910, A. Dunin-Gorkavich published Russko-ostyatsko-samoyedskiy prakticheskii slovar’ naiboleye upotrebitel’nykh slov (Russian-Ostyak-Samoyedic Practical Dictionary of the Most Commonly Used Words). All the editions, except for Witsen’s book, used Cyrillic-based writing.

The system of writing of Tundra Nenets began to fully function in 1931, when the first Latin-based Nenets alphabet was approved. The writing was based on the Bolshezemelsky dialect which occupies a central place among the Tundra Nenets dialects from a geographic point of view. In 1932–1933, there was published the Nenets ABC called Jadəj wada (New word) compiled by G. Prokofiev. Since 1932, there were periodical publications in Tundra Nenets in the Narjana wьnder newspaper (Red tundra-dweller, Naryan-Mar), and since 1933, in the Narjana Ŋərm newspaper (Red North, Salekhard). Several schoolbooks and teaching aids for primary schools, as well as translations of several works of Russian writers and ideological booklets were published between 1932 and 1936. In 1937, a new Cyrillic-based alphabet for Tundra Nenets was approved. It used the key principles of graphics of the Russian language, but had additional graphemes for the specific Tundra Nenets sounds and diacritical marks to indicate long and short vowels.

Modern alphabet of Tundra Nenets:

Аа, Бб, Вв, Гг, Дд, Ее, Ёё, Жж, Зз, Ии, й, Кк, Лл, Мм, Нн, Ңң (Ӈӈ), Оо, Пп, Рр, Сс, Тт, Уу, Фф, Хх, Цц, Чч, Шш, Щщ, ъ, Ыы, ь, Ээ, Юю, Яя.

-

3. Geographic Characteristics

3.1.

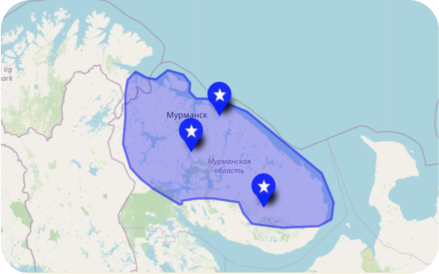

The territory predominantly inhabited by Tundra Nenets is divided between four subjects of the Russian Federation: Nenets Autonomous Okrug of Arkhangelsk Oblast (7.504 men), the northern regions of the Republic of Komi (503 men), Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug of Tyumen Oblast (28.222 men), and Tamyrski Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai (3.494 men). Based on the 2010 Census, Tundra Nenets accounted for 18% of the population of Nenets Autonomous Okrug, 6% of Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, and 10% of Tamyrski Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai.

3.2. Total Number of Traditional Native Settlements

At present, there are 75 localities traditionally inhabited by the Tundra Nenets speakers. Below, you’ll find the estimated Tundra Nenets population for the regions inhabited by both Tundra and Forest Nenets (N. B. the ≈ symbol in the tables 2 and 3) based on the data by E. Volzhanina regarding the population and distribution of Forest Nenets.

List of Settlements

Nat. — Nenets nationality

PR — indicated proficiency in Nenets

NL — indicated Nenets as their native language

|

Subject and district / region

|

Type of locality

|

Locality

|

Total, men

|

Nat.

|

%

|

PR

|

%

|

NL

|

%

|

|

Nenets Autonomous Okrug

|

|

|

hamlet

|

Chernaya

|

5

|

4

|

80

|

4

|

80

|

|

0

|

|

town

|

Khorey-Ver

|

739

|

345

|

47

|

0

|

0

|

21

|

3

|

|

town

|

Vyucheysky

|

167

|

107

|

64

|

6

|

3,6

|

7

|

4

|

|

town

|

Indiga

|

632

|

339

|

54

|

68

|

11

|

109

|

17

|

|

hamlet

|

Kiya

|

63

|

51

|

81

|

10

|

16

|

4

|

6

|

|

hamlet

|

Chizha

|

99

|

36

|

36

|

0

|

0

|

13

|

13

|

|

town

|

Shoyna

|

300

|

44

|

15

|

8

|

2,7

|

6

|

2

|

|

village

|

Nes

|

1368

|

669

|

49

|

23

|

1,7

|

458

|

33

|

|

hamlet

|

Belushye

|

50

|

4

|

8

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

hamlet

|

Verkhnyaya Pesha

|

134

|

6

|

4,5

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

hamlet

|

Vizhas

|

75

|

24

|

32

|

0

|

0

|

10

|

13

|

|

hamlet

|

Volokovaya

|

105

|

10

|

9,5

|

0

|

0

|

5

|

5

|

|

hamlet

|

Volonga

|

35

|

3

|

8,6

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

hamlet

|

Oma

(Рис. 39–41)

|

763

|

376

|

49

|

123

|

16

|

108

|

14

|

|

hamlet

|

Snopa

|

99

|

74

|

75

|

5

|

5,1

|

|

0

|

|

village

|

Nizhnyaya Pesha

|

718

|

70

|

9,7

|

4

|

0,6

|

4

|

1

|

|

town

|

Bugrino

|

424

|

385

|

91

|

57

|

13

|

353

|

83

|

|

town

|

Kharuta

|

538

|

177

|

33

|

0

|

0

|

4

|

1

|

|

город

|

Naryan-Mar

|

21658

|

1283

|

5,9

|

115

|

0,5

|

206

|

1

|

|

hamlet

|

Andeg

|

175

|

59

|

34

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

hamlet

|

Kamenka

|

121

|

23

|

19

|

0

|

0

|

13

|

11

|

|

hamlet

|

Кuуя

|

86

|

18

|

21

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

hamlet

|

Pylemets

|

44

|

11

|

25

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

hamlet

|

Ustye

|

22

|

8

|

36

|

0

|

0

|

|

0

|

|

town

|

Krasnoye

(Рис. 46)

|

1519

|

802

|

53

|

286

|

19

|

280

|

18

|

|

town

|

Nelmin Nos

|

916

|

798

|

87

|

0

|

0

|

757

|

83

|

|

town

|

Khongurey

|

230

|

113

|

49

|

10

|

4,3

|

25

|

11

|

|

village

|

Telviska

|

454

|

42

|

9,3

|

5

|

1,1

|

|

0

|

|

town

|

Amderma

|

539

|

249

|

46

|

6

|

1,1

|

207

|

38

|

|

town

|

Karataika

|

544

|

266

|

49

|

13

|

2,4

|

84

|

15

|

|

town

|

Ust-Kara

|

574

|

440

|

77

|

8

|

1,4

|

8

|

1

|

|

town

|

Varnek

|

101

|

98

|

97

|

|

|

|

0

|

|

Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

|

|

|

Nadymsky District

|

town

|

Kutopyugan

|

812

|

660

|

81

|

524

|

65

|

648

|

80

|

|

Nadymsky District

|

town

|

Nori

|

360

|

219

|

61

|

207

|

58

|

207

|

58

|

|

Nadymsky District

|

town

|

Nyda

|

1794

|

992

|

55

|

585

|

33

|

797

|

44

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Aksarka

|

3115

|

533

|

17

|

319

|

10

|

267

|

9

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Beloyarsk

|

1848

|

750

|

41

|

490

|

27

|

433

|

23

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Gornoknyazevsk

|

120

|

9

|

8

|

9

|

8

|

4

|

3

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

hamlet

|

Laborovaya

|

669

|

653

|

98

|

598

|

89

|

657

|

98

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Tovopogol

|

111

|

27

|

24

|

15

|

14

|

6

|

5

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

village

|

Khalas’pugor

|

41

|

25

|

61

|

11

|

27

|

15

|

37

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Chapaevsk

|

27

|

|

|

4

|

15

|

|

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Shchuch'ye

|

847

|

814

|

96

|

803

|

95

|

809

|

96

|

|

Priuralsky District

|

town

|

Yambura

|

90

|

32

|

36

|

33

|

37

|

25

|

28

|

|

Purovsky District

|

village

|

Samburg

|

1921

|

1444

|

75

|

1210

|

63

|

1210

|

63

|

|

Tazovsky District

|

small town

|

Tazovsky

(Рис. 47)

|

6794

|

1636

|

24

|

423

|

6

|

1289

|

19

|

|

Tazovsky District

|

village

|

Antipayuta

|

2546

|

2144

|

84

|

2148

|

84

|

2148

|

84

|

|

Tazovsky District

|

village

|

Gyda

(Рис. 48–52)

|

3329

|

3047

|

92

|

3041

|

91

|

3041

|

91

|

|

Tazovsky District

|

hamlet

|

Matyuy-Sale

|

7

|

7

|

100

|

7

|

100

|

7

|

100

|

|

Tazovsky District

|

village

|

Nakhodka

|

1203

|

1168

|

97

|

1157

|

96

|

1157

|

96

|

|

Tazovsky District

|

hamlet

|

Tibei-Sale

|

718

|

708

|

99

|

708

|

99

|

710

|

99

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

town

|

Yar-Sale

|

6484

|

3809

|

59

|

3507

|

54

|

3643

|

56

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

town

|

Mys-Kamenny

|

1614

|

367

|

23

|

361

|

22

|

362

|

22

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

town

|

Novy Port

|

1783

|

1303

|

73

|

1187

|

67

|

1277

|

72

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

town

|

Panayevsk

|

2267

|

1731

|

76

|

1797

|

79

|

1698

|

75

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

hamlet

|

Ports-Yakha

|

11

|

11

|

100

|

11

|

100

|

11

|

100

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

village

|

Salemal

|

967

|

316

|

33

|

346

|

36

|

307

|

32

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

village

|

Seyakha

(Рис. 53–59)

|

2602

|

1863

|

72

|

2031

|

78

|

2114

|

81

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

town

|

Syunai-Sale

|

444

|

429

|

97

|

437

|

98

|

428

|

96

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

hamlet

|

Tambei

|

33

|

30

|

91

|

30

|

91

|

29

|

88

|

|

Yamalsky District

|

town

|

Yaptik-Sale

|

62

|

62

|

100

|

62

|

100

|

62

|

100

|

|

Salekhard

|

city

|

Salekhard

|

42527

|

1182

|

3

|

328

|

1

|

689

|

2

|

|

Nadym

|

city

|

Nadym

|

46562

|

505

|

1

|

264

|

1

|

275

|

1

|

|

Krasnoyarsk Krai

|

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Nosok

|

1692

|

1434

|

85

|

1354

|

80

|

1404

|

83

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Tukhard

(Рис. 60–63)

|

814

|

726

|

89

|

651

|

80

|

732

|

90

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

city

|

Dudinka

|

22204

|

782

|

3,5

|

368

|

1,7

|

248

|

1

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Ust-Port

|

338

|

192

|

57

|

0

|

0

|

137

|

41

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Vorontsovo

|

253

|

161

|

64

|

52

|

21

|

111

|

44

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Karaul

|

801

|

246

|

31

|

27

|

3,4

|

100

|

12

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Baykalovsk

|

122

|

105

|

86

|

58

|

48

|

53

|

43

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Polikarpovsk

|

33

|

21

|

64

|

33

|

100

|

21

|

64

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Kazantsevo

|

17

|

17

|

100

|

0

|

0

|

17

|

100

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Mungui

|

11

|

11

|

100

|

11

|

100

|

11

|

100

|

|

Taimyrsky District

|

town

|

Potapovo

|

334

|

69

|

21

|

16

|

4,8

|

10

|

3

|

Below, find the estimated Tundra Nenets population for the regions inhabited by both Tundra and Forest Nenets (N. B. the ≈ symbol in the tables 2 and 3) based on the data by E. Volzhanina regarding the population and distribution of Forest Nenets.

Total population of Tundra Nenets in the subjects of the Russian Federation, based on the article by S. Burkova on Tundra Nenets, Yazyk I Obshestvo (Language and community, 2016)

|

Registration of representatives of the ethnic group

|

Population of the ethnic group, based on the 2010 Census

|

|

Number of people

|

% of total population of the subject

|

|

Murmansk Oblast

|

149

|

0,02 %

|

|

Arkhangelsk Oblast, incl.

Nenets Autonomous Okrug

|

8020

7504

|

0,65 %

17,8 %

|

|

Republic of Komi

|

503

|

0,06 %

|

|

Tyumen Oblast, incl.:

Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug-Yugra

|

≈ 29621

≈ 28222

≈ 988

|

≈ 0,87 %

≈ 5,4 %

≈ 0,06 %

|

|

Krasnoyarsk Krai, incl.:

Taimyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District

|

3633

3494

|

0,1 %

10,1 %

|

|

St. Petersburg

|

109

|

0,002 %

|

|

Other RF regions

|

605

|

―

|

Total number of Tundra Nenets speakers in the subjects of the Russian Federation, based on the article by S. Burkova on Tundra Nenets, Yazyk I Obshestvo (Language and community, 2016)

|

Registration of speakers

|

Number of speakers, based on the 2010 Census

|

|

number of people

|

%

|

|

Murmansk Oblast

|

2

|

1,3 %

|

|

Arkhangelsk Oblast, incl.

Nenets Autonomous Okrug

|

828

750

|

10,3 %

10 %

|

|

Republic of Komi

|

243

|

48,3 %

|

|

Tyumen Oblast, incl.:

Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug

Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug-Yugra

|

≈ 15788

≈ 15640

≈ 62

|

≈ 53,2 %

≈ 55,4 %

≈ 6,2 %

|

|

Krasnoyarsk Krai

|

1650

|

45,4 %

|

|

St. Petersburg

|

29

|

26,6 %

|

|

Other RF regions

|

57

|

9,4 %

|

The number of native speakers and corresponding ethnic group based on various censuses (starting from 1897) and other sources

|

Census Year

|

Number of native speakers (men)

|

Size of ethnic group (men)

|

Comments

|

|

1897

|

3940

(European Samoyeds)

5371

(Yuraks)

|

―

―

|

|

|

1926

|

17817 (Samoyeds)

2101

(Yuraks)

|

15456

(Samoyeds)

2104

(Yuraks)

|

In the conclusions, Yurak is included into Samoyed (= Nenets).

|

|

1959

|

19481

|

23000

(Nenets)

|

Language of respondent’s nationality (ethnic group), i.e. without taking into account proficient people from other ethnic groups

|

|

1970

|

24186

|

29000

(Nenets)

|

Language of respondent’s nationality (ethnic group), i.e. without taking into account proficient people from other ethnic groups

|

|

1979

|

24395

|

29894

(Nenets)

|

Including the language of respondent’s nationality (ethnic group) as a second language

|

|

1989

|

27273

|

34665

(Nenets)

|

Including the language of respondent’s nationality (ethnic group) as a second language

|

|

2002

|

31311

|

41302

|

|

|

2010

|

23404

(speaking Tundra Nenets)

20826

(indicated proficiency in Tundra Nenets)

33385

(indicated Tundra Nenets as native language)

≈ 18597, based on [Burkova 2016: 318]

|

41820

≈ 42640, based on [Burkova 2016: 316]

|

In some traditional localities (for instance, Gyda and Antipayuta of the Tazovsky District and Nori of the Nadymsky District, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug), the command of Tundra Nenets was next to nil, based on the 2010 Census, although it was indicated as native language by the majority of inhabitants. Thus, it means that the respondents or census takers did not necessarily indicate their native language as the one they were fluent in.

|

|

2020

|

23 506 respondents that indicated their proficiency in Tundra Nenets

|

49787

total Nenets

|

|

-

1. Position in the Genealogical Classification of World Languages

2.1. Dialect division of Tundra Nenets

Uralic family > Samoyedic strand > Northern Samoyedic group

Along with the closely related Forest Nenets (Neshan), Tundra Nenets language belongs to the Northern group of the Samoyedic strand of the Uralic language family.

The

Western

dialect group comprises three Far Western and one Western dialects. The Far Western dialects include

Kanin

(Kanin Peninsula and the mainland of the Kanin Tundra from the Konushinsky shore of the Mezen Bay in the west up to the Pesha River in the east),

Timansky

(Timanskaya Tundra located between the Pesha River in the west and the Indiga River in the east), and

Kolguyevsky

(on the Kolguyev Island in the Barents Sea). The Western dialect is

Malozemelsky

(Malozemelskaya Tundra located between the Indiga River in the west and the Pechora River in the east).

The

Central

dialect group comprises the subdialects of Bolshezemelsky dialect (Bolshezemelskaya Tundra located between the Pechora River in the west and the Pai-Khoi Ridge and the Ural Mountains in the east).

The

Eastern

(or Siberian) dialect group includes the Eastern (to the west from the Ob River and the Gulf of Ob:

Priural

and

Yamal

) and Far Eastern dialects (to the east from the Gulf of Ob:

Nadym, Taz, Gydan, and Taimyr

= Yenisei). Many dialects of Tundra Nenets are further divided into subdialects: Yamal dialect, for instance, can be divided into Yar-Salinsky, Panaevsky, Novoportovsky, Yaptiksalinsky, Seyakhinsky, Tambei, and other subdialects.

The Tundra Nenets literary language is based on the Bolshezemelsky dialect that occupies a central position in the dialect continuum (with some elements of the Yamal dialect as well).

Among the facts that affect the range of dialect continuum, on should point out the contacts between Tundra Nenets, on one hand, and the dialects of Komi и Khanty languages in the Bolshezemelsky and Priuralsky Tundras, on the other, as well as the Nenets-Enets contacts in the lower reaches of the Yenisei river.

There is a view that despite a wide geographic distribution of Tundra Nenets, its dialects are relatively uniform and the speakers of outlying dialects understand each other without any difficulty. In spite of the fact that the speakers of different Nenets dialects indeed can understand each other, they are easily aware of phonetic dialect differences and notice the abnormalities in the speech of not only remote representatives of their ethnic group, but even their closest neighbors. We have heard Kanin Nenets say on numerous occasions that the pronunciation of inhabitants of Indiga in the Timansky Tundra was “hard” and “different”, not to mention the speakers from Bolshezemlsky and Yamal Tundras that they had to communicate with during their studies in Naryan-Mar or Salekhard. As for Koluyevsky Nenets, they describe the pronunciation of Kanin and Timannsky Nenets as “hard”.

It is just as interesting to analyze the mutual appreciations of speech peculiarities between the speakers of Yamal, Gydan, and Taimyr (Yenisei) dialects that often imitate and even exaggerate in a joking manner the way the speakers of adjacent idioms tend to pronounce words. For instance, Yamals imitate the lisping pronunciation of the sibilant

cʹ

, typical of the Far Eastern dialects. Cf. also a snippet of the transcript concerning the description of the Gydan dialect by Taimyr (Yenisei) speakers:

«А с Гыды́ вот

<...>

.

Ну, у них язык тоже друговáтый, не такой, как у нас. Ну, язык другой

―

такой, ну, как акцент у них»

(And as for Gyda, here you go<...> Well, their language is somewhat different, not like ours. Well, the language is different, you know, like they have an accent)(informant I. Vengo, 2017).

The Far Western dialects – Kanin, Timansky, and Kolguyevsky – are particularly different from other dialects of Tundra Nenets. It is typical for all Western dialects not to have the phoneme of

ŋ

in the initial syllable of a word (

əno

[boat],

arka

[big],

uda

[hand]), contrary to Central, Eastern, and Far Eastern dialects (

ŋəno

/

ӈăно

[boat],

ŋarka

/

ӈарка

[big],

ŋuda

/

ӈуда

[hand]). It can be considered the most obvious and striking difference of Western dialects from the Tundra Nenets literary language.

The most striking feature of Eastern dialects, probably, is to pronounce

ц

as

ч:

the change of affricate [t͡sʲ] (in spelling

ць

, in phonological representation

с

ʹ

) to [t͡ɕ] (iit can be written down as

чь

). The lisping – the change of a voiceless soft (palatal) fricative [sʲ] (

сʹ

) to [ʃ] (

ш

) – is typical of the Far Eastern dialects (Gydan and Taimyr), but does not occur neither in Western nor in Central idioms or in the Eastern idioms situated to the west from the Gulf of Ob (not even in Yamal dialect). Subsequently, one can observe the change of [d] to [ð] or [z] (fricativization) and the change of [tʲ] to the

affricate [t͡ɕ] (affrication of a stop) only in Taimyr dialect, as well as its neighboring Gydan dialect (but less consistently and to a lesser degree).

Brief

History of Studying the Language

The first information about the Nenets language dates back to the late 16th – early 17th centuries. In can be found in the descriptions of journeys across Siberia and the European North of Russia, in the documents of management and record keeping compiled during the accession of Siberia to Russia, as well as in Kniga bol’shomu chertezhu (The Book of the Great Map, 1627) — a detailed cartographic description of the Russian state. In the 18th – beginning of the 19th centuries, various lists of Tundra Nenets words compiled by the members of scientific expeditions to the northern territories of the Russian state were published: Daniel Gottlieb Messerschmidt, Philip Johan von Strahlenberg,

Gerhard Friedrich

Müller, Peter Simon Pallas, Vasily Zuyev, Anders Johan Sjögren, Alexander Theodor von Middendorff, and others. In the 1780s, Catherine II ordered to collect materials for

Sravnitel’niye slovari vsekh yazykov i narechiy

(Comparative Dictionaries of All Languages and Dialects). In 1787, the first volume of the dictionary covering European and Asian languages saw the light of day, edited by P. S. Pallas and accompanied with his foreword. Under the numbers 120–129, it listed the words of 10 geographic varieties of Tundra Nenets. In 1811, German linguist Johann Severin Vater made an attempt to compile the grammar of Tundra Nenets.

In the early 19th century, missionary schools designed to educate local population began to open in the Far North. Priests compiled dictionaries and grammars of indigenous languages, including Tundra Nenets. Archimandrite Veniamin (mundane name Vasily Smirnov, 1782–1848) preached Christianity (Orthodox) among Nenets (Samoyeds) in Mezensky uyezd in the north of Arkhangelsk Province. As part of his missionary work, Archimandrite Veniamin actively learned Tundra Nenets (its Western dialects), compiled a dictionary called

Лексикон самоедского языка

(Lexicon of Samoyedic Language), translated into Tundra Nenets the New Testament, catechism, and certain prayers, and also prepared

Грамматика самоедского языка

(Grammar of Samoyedic Language).

From summer 1842 to January 1849, M. Kastren took a number of trips across the north of the European part of Russia and Siberia, where he undertook a linguistic analysis of various regions of residence of Nenets and other Samoyed peoples. He managed to compile an extensive collection of materials on phonetics, grammar, and vocabulary of Samoyedic languages and dialects (including Tundra Nenets), as well as some other languages of the North of Russia. Kastren’s

Grammatik der samojedischen Sprachen

(Grammar of Samoyedic Languages) was the first academic grammar of Samoyedic languages. In the 1910s, Finnish researcher Toivo Vilho Lehtisalo continued to study Nenets. Among his Nenets-related publications, one should point out the collection of Nenets folklore that he compiled (1947) and

Juraksamojedisches Wörterbuch

(Yurak-Samoyedic Dictionary, 1956).

A very important contribution to the Tundra Nenets studies was made by the distinguished researcher G. Prokofiev and his students A. Pyrerka, G. Verbov, and N. Tereschenko. The lexicographic activities of N. Tereschenko are particularly noteworthy: she compiled five Nenets dictionary, including a very unique and valuable one. We are talking about

Ненецко-русский словарь

(Nenets-Russian Dictionary) that contains about 22.000 words, including a short grammatical essay on Nenets (1965, reedited in 2003). To date, it is the most voluminous dictionary of Tundra Nenets. Various aspects of the Tundra Nenets studies were covered by A. Scherbakova, Z. Kuprianova, L. Khomich, M. Barmich, Y. Popova, E. Khelimsky, K. Labanauskas, M. Lyublinskaya, E. Pushkareva, L. Nenyang, G. Vanuito, R. Laptander, etc. The dialectological dictionary edited by N. Koshkareva (Dialektologicheskiy slovar’ nenetskogo yazyka (Nenets Dialectological Dictionary, 2010), contains data on modern dialects of Tundra Nenets collected during the expeditions across the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. In 2014, I. Nikolaeva published A Grammar of Tundra Nenets, a very detailed grammatical description of Tundra Nenets.

Outside of Russia, there were other researchers that actively studied Tundra Nenets and other Samoyedic languages: J. Niemi, J. Alatalo, P. Hajdú, T. Mikola, J. Pusztay, D. Decsy, J. Janhunen, A. Kyunnap, etc. Tapani Salminen made a significant contribution to the studies of Tundra Nenets phonology, morphophonology, and morphology. His Morphological dictionary of Tundra Nenets (1998) provides insight into grammatical characteristics of Nenets words (alternations during the declension of nouns, types of verb conjugation, etc.).

Thus, the history of Tundra Nenets studies is already nearly 170 years old. The bibliography of these studies covering different aspects includes over 400 publications, there are more than 10 grammatical profiles of various sizes. Yet, we still cannot claim that we have sufficient knowledge of Tundra Nenets.

It is typical for the phonetics of Tundra Nenets to have the opposition of “soft and “hard” consonants (correlation of palatalization), as well as voiced and voiceless consonants, the absence of consonant clusters in the initial syllable of a word in traditional Nenets words, the use of reduced vowels in the non-initial syllables.

In terms of morphology, Tundra Nenets is an agglutinative type of language with certain elements of internal inflection. There is virtually no prefixation. Tundra Nenets has the so-called predestinative forms of nouns, as well as dual numbers. Nouns can create predicative forms by changing in person, number, and tense. There are three types of conjugation within Tundra Nenets: subjective, objective (with the indicated number of objects), and reflexive. It is typical for Tundra Nenets to have affixes designed to express aspectual and evidential meaning, as well as modal value.

Syntactically, Tundra Nenets is a nominative language with a relatively stable SOV word order (subject ― object ― predicate, subject ― objective complement ― verb).