Institute of Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences

О. Krylova

Mednyj Aleut

I. Sociolinguistic Data

Mednyi Aleuts (MA) call their language алеуутам умсуу [language of Aleuts] (cf. унаӈам умсуу [language of Aleuts] in Bering Aleut).

I. 2. General Characteristics

2.1.

Total Number of Speakers and Their Ethnic Group

Currently, the Mednyi Aleut group is on the brink of extinction. Today, there is only one adult who speaks the MA language fluently – Lydia Volkova (Fedoseeva), who lives in Nikolskoye on Bering Island (part of the Commander Islands group, similar to Mednyi Island). Another MA native speaker Gennady Yakovlev passed away on October 4, 2022.

The Aleuts that currently live on Bering Island are divided by origin into two groups: Mednyi Aleuts and Bering Aleuts. The former used to live in Preobrazhenskoye on Mednyi Island until the late 1960s. During the Soviet campaign of consolidation of rural settlements, they were relocated to Nikolskoye on Bering Island. The population of Mednyi Island amounted to 274 people in 1890, and only 171 people in 1920. In addition to L. Volkova, another two or three people aged over 60 can say a few words or phrases, but they are incapable of carrying on a real conversation.

I.2.3. Sociolinguistic Characteristics

I.2.3.1. Threat of Extinction

MA can be considered virtually extinct. It was badly affected when the compact living of native speakers was disrupted and all the inhabitants of Mednyi Island were relocated to Bering Island. The relocation resulted in a deep psychological trauma for the community that had always possessed its own identity, completely independent from Bering Aleuts. It was based on a number of specific cultural practices (mainly defined by the unique natural environment of Mednyi Island), as well as the use of their language. Their move to a relatively big settlement such as Nikolskoye, where Mednyi Aleuts (even together with Bering Aleuts) were in the minority, had considerably sped up the language shift, as a result of which there was but one single MA native speaker left by the end of 2022. No system of writing was created for Mednyi Aleut.

I.2.3.2. Use in Various Spheres

|

Sphere

|

Use

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

RF: no

|

|

Education: nursery school

|

no

|

|

Education: school

|

RF: no

|

|

Education: higher education

|

no

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

no

|

|

Media: press (incl. online editions)

|

no

|

|

Media: radio

|

no

|

|

Media: TV

|

no

|

|

Culture (incl. live folklore)

|

no

|

|

Fiction in native language

|

no

|

|

Religion (use in religious practice)

|

no

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Justice system

|

no

|

|

Agriculture (incl. hunting, gathering, reindeer herding, etc.)

|

no

|

|

Internet (communication/ existence of websites in native language, not media)

|

no

|

I.3. Geographic Characteristics

I.3.1.

Subjects of the Russian Federation with compact residence of native speakers

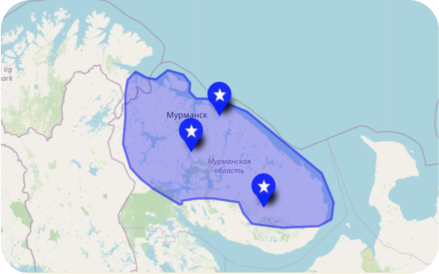

The main area of compact residence of native speakers is the Aleut district in Kamchatka Krai.

I.4. Historical Dynamics

The Aleut language from Mednyi Island, uncovered for linguistics by G. Menovschikov during his 1963 expedition on the Commander Islands is a result of merging of two languages, Aleut and Russian. Although the origins of nearly all parts of the MA structure can be easily identified, Mednyi Aleut is an independent language system that became distinct from its source languages.

In general, MA is a very rare linguistic phenomenon. The language belongs to a recently identified class of mixed languages. Their peculiarity is that a big part of their grammar structures originates from one language, whereas vocabulary, from another one. There are barely three dozens of mixed languages in the world. Although their number is small, they do exist on all continents, which attests to the productivity of this building mechanism (grammar from one language, vocabulary from another one) that can be seen in verbal improvisations.

The sociolinguistic conditions of emergence of Mednyi Aleut were determined by the appearance of a new (ethnic) group, the Creoles. The name of Creole (the official name used in the documents of the Russian-American Company that was in full control of Alaska until its sale in 1867) described the descendants of marriages between Russian industrialists and Aleuts. Creoles had a formal social status and were intermediaries between Russians and Aleuts. Prior to the appearance of Mednyi Aleut, they were all bilinguals, i.e., fluent in both Aleut (their native language) and Russian. It is quite possible that the new language managed to develop, stabilize, and become a tool of intra-group communication solely because it was yet another ethnic marker, quite probably the most important one. The stories of descendants of Creoles and Aleuts recorded during the Alaska field studies in 2008 confirmed the importance of their status differences that persisted long after the dissolution of the Russian-American Company.

It is unclear where Mednyi Aleut first emerged. We know, however, that during the relocation of the Aleutian ridge population to the Commander Islands, the strands of the language appeared. The resettlement was initiated by the Russian-American Company that controlled the entire territory of Alaska and Aleutian Islands. The purpose of this relocation was to begin hunting sea otters and other sea animals in hitherto uninhabited places. The language of the Aleut population relocated from Bering Island was completely identical to Aleut from Atka island. Whereas people from Mednyi Island spoke the language that had never been recorded before, Mednyi Aleut. The MA structure analysis shows that the Aleut part of this mixed language can be traced back to the Aleut dialect of Attu island that completely disappeared in the 20th century. It seems quite likely that MA appeared either on Attu island or later on Mednyi Island, if the majority of the relocated Aleut population were originally from Attu island.

II. Linguistic Data

II.1.

Position in the Genealogical Classification of World Languages

In terms of structure, MA is a unique phenomenon. It resulted from the merging of two languages (in this particular case, Aleut and Russian). This makes it part of a special group of languages called mixed or intertwined. Since the structure of all mixed languages clearly comprises the components of two languages, their genealogical classification is somewhat problematic.

II.2. Dialects

There are no MA dialects. The hypothesis about Bering Aleut and Mednyi Aleut being dialects of the same language turns out to be untenable due to the special nature of MA (mixed language).

II.3. Key Linguistic Data

Due to the specific nature of MA, its main features should be analyzed in terms of their origins. Aleut was the source of demonstrative pronouns, postpositions, nominal inflection system, nominal and verbal word-formation, several dependent verb forms, a greater part of lexical structure (nouns and verbs). Russian provided verbal inflection (tenses, persons, optionally genders), infinitive (Aleut does not have this form), negative indicator, future tense construction, conjunctions, subject pronouns, particles, adverbs, most of syntactic constructions.

Although the origins of nearly all parts of the MA structure can be easily identified, Mednyi Aleut is an independent language system that cannot be reduced to any of the source languages. When analyzing the correlation between Russian and Aleut components of Mednyi Aleut, it should be noted that from a typological point of view, Aleut is more predominant than Russian. The Mednyi Aleut phonological system is a compromise between Aleut and Russian systems, but with a predominance of Aleut elements. In the case of its morphology that is primarily based on agglutination, the prevalence of Aleut features is particularly noticeable. As for syntax, it is also a compromise between two languages, but this time Russian is playing a somewhat bigger part. However, even in this case Mednyj Aleut maintained some fundamentally important syntactic mechanisms of Aleut. Still, the most crucial evidence of the typological predominance of Aleut compared to Russian is the very fact that absolutely every Aleut component of Mednyi Aleut remains unaltered, identical to its equivalent within Aleut (with the exception of phonological system), whereas virtually all elements of Russian origin are distorted to a certain extent or greatly simplified. This may lead to the conclusion that the “creators” of Mednyi Aleut might have been native Aleut speakers that were proficient in Russian as their second language. We may be talking about the existence of a special variant of Russian language in the Russian America of the 19th century, the equivalent of what Creole Studies call interlanguage. That would explain the deviation of the Russian component of Mednyi Aleut from its standard version.

All MA linguistic levels exhibit a high degree of variability. Indeed, MA has some core areas that are not subject to variability, while some others allow for a free choice of one of the synonymic variants, a sort of etymological doublets, based on one of the source languages. Perhaps, the norm for Mednyi Aleut used to be a more Aleut-like variant, and its greater Russification took place only recently due to the complete dominance of Russian and the imminent language death of Mednyi Aleut.

II.4.1. Phonetics

A considerable part of its phonemic inventory comprises phonemes that are common (close) to both Aleut and Russian. Some phonemes – the so-called voiceless sonorants (at present, only elder native speakers still use them in their speech) and uvulars – are specific to Aleut. Under the influence of Russian, Aleut words of the MA began to feature labials: stops such as /п/, /б/ and fricatives /ф/ and /в/, plus, /п/ and /б/ in Aleut words resulted from the restructuring of the bilabial /w/ from the Attuan dialect. Some of native speakers begin to consider it optional to oppose uvular and velar sounds. The Russian words that entered Mednyi Aleut only recently maintain their palatalization, which is unusual for any “pure” Aleut dialect. In general, all words adopted from Russian in the recent period underwent virtually no phonetic adaptation at all. It can be said that two phonological systems, Aleut and Russian, coexist within the MA phonological space. This is the fundamental difference between MA and numerous Creole languages that formed their own phonological system.

Morphology

When it comes to compounds, MA belongs to agglutinative languages. Similar to Aleut, it is prefixless. The only exception is the negative indicator (from the Russian particle не) preceding a verb.

Parts of speech. They distinguish the following parts of speech: nouns, pronouns, verbs, numerals, demonstrative pronouns, interrogative pronouns, postpositions, adverbs, conjunctions, particles, interjections.

MA inherited all the grammatical categories for nouns from the Attuan dialect of Aleut. There are three grammatical numbers for nouns: singular ахсину-х' [girl], dual ахсину-х [two girls], plural ахсину-н [girls]. Similar to all Aleutian dialects, MA has two cases. Compared to Aleut, the ablative case (singular -м; dual -х; plural -н) has one less function: it only marks the possessor noun in a possessive combination (both MA and Aleut have no adjectives, and any attributive relation is transmitted by a possessive combination of two nouns, the same way that forms the combination of noun and postposition): собака-м hитхии [dog’s tail], анг'аг'ина-н улан'и [people’s houses], ах'сааг'а-м амайакнаа [a contagious disease, or literary bad disease], ула-м 'айа [to the house]. MA also has a second ablative case with an indicator that marks the possessor in a trinomial possessive combination, when it is simultaneously a possessee: уухозам hузу-ган илин'и [on all hunting grounds]. MA and Aleut have the same system of possessive markers for 1st, 2nd, 3rd person, and 3rd person coreferential: аxсину-н' [my daughter], аxсину-ун [your daughter], аxсину-у [his daughter], etc. The paradigm of possessive indicators was inherited from Aleut.

MA kept the same system of nominal derivational suffixes as Aleut: аxсину-куча-н' [my little daughter], анг'аг'ина-чхиза-х' [a good man], ига-аси-х' [a wing], ун'учи-илуг'и-х' [seat, chair], etc.

Pronouns. All personal pronouns that can act as a subject (subject pronoun) or a complement (object pronoun) with the verb-predicate are of Russian origin (Table 3).

Table 3. Personal and reflexive pronouns

|

|

Subjective

|

Objective

|

Reflexive

|

|

Singular

|

Plural

|

Singular

|

Plural

|

Singular

|

Plural

|

|

1st p.

|

я

|

Мы

|

меня

|

нас

|

тин

|

тимас/тимис

|

|

2nd p.

|

ты

|

Вы

|

тебя

|

вас

|

тин

|

тичи

|

|

3rd p.

|

он/она

|

Они

|

его/ее

|

их

|

тин

|

тичи

|

N.B. All words of Russian origin (except for the loanwords that penetrated all Aleut dialects at the earliest stage of contacts between Aleuts and Russians, and underwent a complete phonetic adaptation) are written down in a traditional orthography (cf. the above-mentioned Table 3 его instead of иво; они instead of ани, etc). Unlike with the old loanwords, Russian dynamic accent here is not interpreted as the Aleut long vowel represented by double letters in writing (cf. modern word проволоках [wire], but old loan word маамкан' [my mother]).

Subjective pronouns can be used in sentences with a predicate in present, past, and future tenses, however there is a trend of not using them in present and future, since finite verb paradigms in such cases make it possible to distinguish between persons (Aleut has no personal pronouns that would act as a subject). In the past tense, the verbal paradigm does not differentiate between persons, so subjective pronouns are always used, unless the person is specified in a context.

MA preserved the Aleut (quasi-)reflexive markers for the 3rd person (reflexive pronouns), cf. the pronoun тин in the following example: айагаа тин ах'сачал [his wife got sick]. Mednyj Aleut kept the Aleut object pronouns for the 1st and 2nd persons that can also be used as reflexive pronouns. In the 3rd person, they might also be replaced by Russian reflexive pronouns: маамкан' укук'ун'и себя ак'ачаали [my mother got her sight back].

The forms of pronouns of both Aleut and Russian origin can be used as an indirect object. Cf. н'ун [that can be translated ‘to me’ or ‘to him’] in the following examples: прооволоках' н'ун к'ан'иий [bend me some wire] or я ему ещо ибйаал [I gave him some more [food]].

MA can also use Russian possessive pronouns that reinforce the meaning of possessive indicators: иглун' у меня 'агал ман гоодах' [my grandson grew up well this year], у него кабии ангийгааит [he’s got a smart head]. In some cases, possessive pronouns are not duplicated by possessive indicators in a noun: у тебя ни бут чугаать к'ичитин [you won’t have enough money].

Verbs have obligatory (grammatical) categories of persons, forms, tenses, and moods that are conveyed via morphological indicators of Russian origin. In the present tense, both categories are conveyed in a syncretic manner (see Table 3). The past tense is marked with the -л indicator; the past tense plural has a special -и marker. In the past tense, person is indicated with personal pronouns (see Table 3), that either play the part of a subject or join the finite verb in an enclitic manner. MA has no grammatical gender, but the -а indicator of female gender in Russian can be optionally used in a verb (only if the speaker is a woman). Examples: аамгих' йуу-ит [blood is flowing] (PRS); укинах' к'ичигаа-ит [knife is sharp] (PRS]; к'игнах' уг'аа-л [the fire went out] (PST); я hусуг'лии-л-(а) [I sneezed] (PST); чиг'анам ила мы ибаг'аа-л-и [we were fishing in a stream] (PST).