Spiritual culture

Kumandins’ traditional religious beliefs are based on their belief in spirits that inhabited the three realms: the heavenly realm, the earthly realms, and the underworld. All spirits were divided into two categories: clean spirits (aryg tos) and unclean spirits (kara tos).

Clean heavenly spirits included clans’ patron spirits (tos or payana): Solu-Kaan was the patron spirit of the Choot seok; Pagdyg-Kaan was the patron spirit of the Tabyska seok; Bay- Ulgen was the patron spirit of the clans Cheley, Chedyber, and Kalar. Bay-Ulgen was the supreme god who had seven or nine sons and seven or nine daughters. Earthly spirits were believed to be clean; they were masters of mountains and waters, the mistress of fire, and patrons of hunting, such as Shalyg, Ulgen’s grandson. Kumandins regularly sacrificed to them; shamans addressed them during their rituals.

Each Kumandin seok had its own sacred mountain, a patroness of the clan. This mountain was home to the clan’s patron spirit. Masters of mountains gave shamans the right to perform rituals. Women were prohibited from being close to their husband’s clan mountains while being bare-headed and barefooted, from going up those mountains, and from saying the mountain’s name out loud.

Unclean spirits lived in the underworld ruled by Erlik, the personification of evil. In addition to Erlik, his sons, and evil spirits from Erlik’s retinue, there were also unclean spirits of each clan. For instance, Yndyrlyg-aza was the unclean spirit of the Shabat seok.

Kurtyyak

or

orokenner

(old women) were a special category of family patrons; those were small rag human-shaped figures (as the

orokenner

of the Cheley seok). Alternatively, they had no images and were known as

kogdy

or

kosh-kelgen

(those who came after). These spirits helped a girl in her new home after marriage.

People communicated with these spirits and the supreme deities Ulgen and Erlik via shamans (kam). Kumandin shamans came in different kinds: “strong” or “medium” shamans could perform rituals using either a drum or a bunch of birch twigs. Shamans played an important role in life cycle rituals and they had to participate in clan sacrifices when a horse would be sacrificed to a seok’s patron spirit (tayelga) and during the kocho-kan erotic ritual.

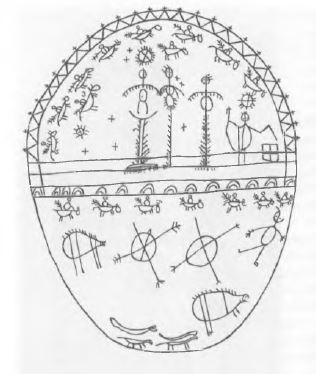

Shamans could perform rituals using a drum (tuur) and a stick (yrbyk/orbo). The drum was perceived as a mount: during the ritual, the shaman would call it alty brkbshtu ak adan, “six- humped sacred camel.” Kumandin drums came in three types depending on their handle shape: mars – “Shor-type” drums with a non-anthropomorphic handle and unique drawings on the outer side of the drum; kanym, drums with the handle in the shape of a two-headed figure; and tezim/chezim, drums with the handle in the shape of a one-headed figure. Some shamans could have several drums at once if the drums were received from different spirits.

There were ritual professionals called, depending on their specialization, different names: yrbykchy, shabychylary (“hitting with a bundle, with a stick”); alaschy, experts in ritual cleansing with fire; kospekchi, or clairvoyants, etc.

Taygam, kanym, shalyg, hunters’ helping spirits, held a prominent place in Kumandins’ traditional religious beliefs: Hunters cut their anthropomorphic images out of wood. From time to time, these spirits were honored with special rituals and sacrifices.

The Kocho-Kan ritual with clear erotic underpinnings and horse sacrifices to a clan’s patron spirit (tayella) were important Kumandin religious rites. Both rituals involved men from a single seok; members of other seoks were not admitted. The principal role was played by the shaman who ensured communication with the spirits of the upper world and “delivered” the soul of the sacrificial animal to the clan’s patron.

The Kocho-Kan was one of the central Kumandin rituals connected with sacrificing a horse. Upper Kumandins performed this ritual in spring, and Lower Kumandins performed it in the fall after the harvest was taken in. During the ritual, the shaman would “bring down” to earth one of the heavenly dwellers, the Kocho-Kan himself who would “possess” one of the men present. This man would put on a mask made of birch bark, take a wooden phallus in his hands, and behave like a rutting stallion trying to touch everyone he met. The incarnated Kocho-Kan went around nearby villages accompanied by a group of men collecting gifts from people, such as food items and tobacco. The spoils were divided between all the participants, and the Kocho- Kan game turned into the tamyr-tomyr song contest. Kumandins revived this ancient ritual in their modern holiday culture and held it, with slight modifications, in October.

In the first half of the 19th century, Kumandins were baptized and were officially listed as Orthodox “newly-baptized non-Slavs.” The Altai spiritual mission was very active among the Kumandins. Orthodox Christianity, however, did not entirely push out traditional beliefs that survive until today in some districts. There are recorded instances of merging Christian and traditional beliefs among Kumandins.