Dolgan Language

Sociolinguistic data

Existing alternative names.

None.

General characteristics

The number of Native Speakers and the Corresponding Ethnic Group.

|

Total size of the ethnic group

|

those who can speak Dolgan (any ethnicity)

|

those who can speak Dolgan

(among Dolgans)

|

|

7885

|

1054

|

930

|

The 2020 Census had 8,182 people call themselves Dolgans, but only 4,836 Dolgan speakers, with 5,413 naming Dolgan as their first language.

Age of speakers

The number of Dolgan speakers is relatively low among young people. It is older people who can speak the language well. Young people feel discouraged from speaking Dolgan not only because they are not fluent, but due to a psychological barrier that exists alongside their command of the language. Above all, the languages of many indigenous minority ethnic groups are associated with traditional culture and folklore, so for many people it is more than simply a communication tool. The Dolgan folklore is varied and rich in its imagery and language, and, therefore, it is vital to preserve the language. At the same time, to do so, a language has to be used not only in the area of traditional culture but in any other area, too. Dolgan provides us with a telling example: Dolgan’s closest relative, Yakut, is one of the ‘strongest’ ethnic languages, functioning successfully and efficiently in the 21st century and spoken by both young people and children. This example proves that nothing in the internal structure of the language prevents it from being used in the present-day world. Dolgan and Yakut are first and foremost different in the number of speakers: Dolgan is spoken by around 1000 people in a linguistic environment dominated by another language, and Yakut is spoken by around 450.000 people.

Sociolinguistic characteristics.

The threat of Extinction

Dolgan is under a severe threat of extinction. The main problem is that the transmission of the language from the older generation to the younger has considerably waned. Initially, the positions of the Dolgan language in Taymyr were quite strong. Even the data as per the latest census (which records a noticeable decrease in numbers of speakers for nearly all the ethnic languages) show that Dolgan is one of the few ethnic languages spoken by representatives of other ethnic groups. In the 21st century, the authorities have to put in extra effort to preserve the linguistic variety and bolster minority languages. These efforts must be directed at developing opportunities for using the language in the present-day world: modern music, SNS texting, websites in a language, etc. Dolgan could have followed the example of the closely related Yakut. For instance, to write in Dolgan on smartphones, one can use a keyboard outlay developed for Yakut.

Use in various fields

|

Area

|

Is it used?

|

|

Family and everyday communication

|

Yes

|

|

Education: kindergartens

|

medium

|

|

Education: school

|

discipline

optional course

|

|

Higher education

|

discipline

|

|

Education: language courses/clubs

|

discipline

|

|

Media: press (including online publications)

|

Yes

|

|

Media: radio

|

Yes

|

|

Media: television

|

Yes

|

|

Culture (including existing folklore)

|

Yes

|

|

Literature in language

|

Yes

|

|

Religion (use in religious practices)

|

Yes

|

|

Legislation + Administrative activities + Courts

|

No

|

|

Agriculture (including hunting, foraging, deer herding, etc)

|

Yes

|

|

Internet (communication/ sites in the language, non-media)

|

Yes

|

Information about a writing system

The current Dolgan alphabet looks like this (the letters in brackets are only used in words borrowed from Russian)

|

А а

|

Б б

|

(В в)

|

Г г

|

Д д

|

(Е е)

|

(Ё ё)

|

(Ж ж)

|

(З з)

|

И и

|

Й й

|

К к

|

Һ һ

|

|

Л л

|

М м

|

Н н

|

Ӈ ӈ

|

О о

|

Ө ө

|

П п

|

Р р

|

С с

|

Т т

|

У у

|

Ү ү

|

(Ф ф)

|

|

(Х х)

|

(Ц ц)

|

Ч ч

|

(Ш ш)

|

(Щ щ)

|

(Ъ ъ)

|

Ы ы

|

Ь ь

|

Э э

|

(Ю ю)

|

(Я я)

|

|

|

It has to be mentioned that the Dolgan spelling system uses the following digraphs (combinations of two letters denoting one sound.

Digraphs дь [d’] and нь [n’] denote palatal consonants, whose location of articulation is the hard palate. They are similar to very soft Russian sounds [d’] and [n’]

Digraphs аа, ии, оо, өө, уу, үү, ыы, ээ denote long vowels.

Digraphs иэ, уо, үө, ыа denote diphthongs.

The Dolgan writing system was created on the Cyrillic basis in the last quarter of the 20th century. The first book to be published was a collection of poems by Dolgan poet Ogdo Aksenova in 1973, well before the official approval of the alphabet in 1979. It is the same alphabet with some slight modifications used nowadays. (Modifications only concern the set of symbols: e.g. the first edition of the alphabet included дь as a separate symbol, whereas the present-day alphabet only has two separate symbols д and ь. But these modifications do not affect the use of digraph дь in practical writing).

Geographic characteristics

Subjects

of

the

Russian

Federation

with C

ompact P

opulation

of N

ative S

peakers

Dolgan is spoken in Taymyr Dolgano-Nenets District of Krasnoyarsk Krai (in settlements along the Rivers Khatanga and Kheta as well as in Anabar National (Dolgan-Evenki) Ulus in Sakha Republic (Yakutia) in settlements of Saskylakh and Yurung-Khaya. Dolgan is also spoken by a part of the Nganasan population of the settlements of Volochanka, Novaya, and Ust-Avam.

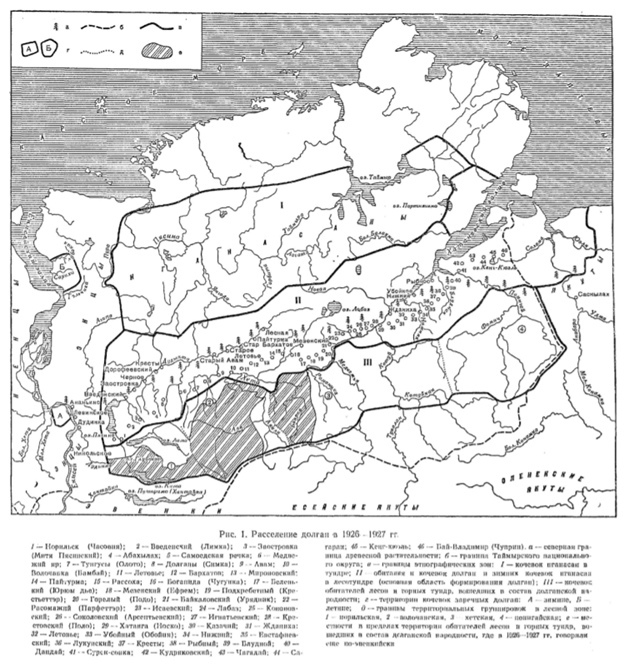

Historical dynamics

Historical dynamics of the size of the ethnic group and Dolgan speakers have some specific features for it is a young ethnic group that took shape only in the 19th century. Thus, Dolgan is a young language. Until around the first quarter of the 20th century, the number of ethnic Dolgans and Dolgan speakers was around the same, but this number did not reach 1000. These low figures likely reflected not the real number of Dolgan speakers, but the unfinished processes of ethnic self-identification. This ethnic self-identification is also linked with treating Dolgan as a separate language rather than the variant of Yakut. So, one has to take into consideration the unreliability of numeric data of the first censuses.

The censuses of the second half of the 20th century recorded a considerable growth of the ethnic group (approximately from 4000 to 7000 people), with 90 percent of them naming Dolgan as their first language. During the first census of the 21st century, in 2002, only 67 percent of Dolgans called Dolgan their native language, which suggests a serious decrease in the number of Dolgan speakers. The 2010 census was the first to separate the questions of which language a person considers to be their native (62 percent of Dolgans replied that Dolgan was their native language) and whether they had mastery of it (only 17 percent of Dolgans did).

There are many understandings of what the term a “native language” implies. Some consider the language a person speaks fluently as a native one because this person learns it from their parents. Many, however, understand the notion of the native language as the language of their ancestors, the language of older people, the language of the ethnic group a person identifies with – which brings about the discrepancy of the numbers between those who consider Dolgan their native language and those who really can speak it.

|

Year of census

|

Number of speakers

|

Size of the ethnic group

|

|

1897

|

967

|

967

|

|

1926

|

653

|

656

|

|

1959

|

3662

|

3900

|

|

1970

|

4380

|

4877

|

|

1979

|

4614

|

5053

|

|

1989

|

5785

|

6945

|

|

2002

|

4865

|

7261

|

|

2010

|

Native language: 4889

mastery of language: 1054

Mastery of language among Dolgans: 930

|

7885

|

|

2020

|

Mastery of language: 4836

Native language: 5413

|

8182

|

Linguistic data

Position in the Genealogical Classification of World Languages

Dolgan along with Yakut makes up a separate branch (sometimes named as North Siberian branch) of Turkic. In fact, Dolgan takes its origin in the Yakut language adopted and adapted by various ethnic groups of different origin. In his book

The Origin of Dolgans,

Boris Dolgikh wrote that Dolgans emerged as a result of the intermixing of multiple groups such as the Evenki, Yakuts, the Enets, and so-called Zatundra peasants (the population of Taymyr).

In Elizaveta Ubryatova’s opinion, Dolgan has been under a “considerable influence of the Evenki language on all its levels” and this linguistic argument corresponds with the hypothesis of the Evenki being the core of what was to become Dolgans. The Dolgan language has a unique position since it emerged in the historical era based on an already existing language, Yakut. Moreover, the linguistic development of Dolgan is not quite ordinary either: as a rule, as scholars think, related languages emerge out of the language splitting into different territorial variants (or dialects otherwise). Gradually these dialects develop independently from each other, diverge, and grow more and more unlike each other, so each of them becomes a separate language. In the case of Dolgan, the origin of the language is different – the language emerged from different ethnic groups adopting Yakut. This non-standard origin of the language explains its special position in the genealogical classification of Turkic languages and poses a question about the age of the Dolgan language. Boris Osipovich Dolgikh in his Origin of the Dolgans, dated the emergence of Dolgans to the 18th or even 19th century. But both Elizaveta Ubryatova and Polish researcher of Dolgan Marek Stachowski argue that B.O. Dolgikh described only the final arrival of the Dolgans as an ethnic group. They think that the emergence of the Dolgan ethnic group and the Dolgan language started much earlier and in a different area: in the 16th-17th cc. in the estuary of the River Vilyuy to the south-east of Taymyr. Marek Stachowski dates the migration of Dolgans from the Vilyuy to Taymyr based on historical documents: in 1628, Dolgans were still living along the Vilyuy, in 1938, they were already in Taymyr. He argues: “the isolation of the Dolgan dialect of Yakut can be dated back to the middle of the 16th century, its final emergence as a separate language – in the middle of the 17th century, that was the time when Dolgans separated from Yakuts and started their own independent life as an ethnos.” Of course, the development of the Dolgan ethnos and the Dolgan language in its present-day form continued in Taymyr and included all the ethnogenetic processes described by B.O. Dolgikh.

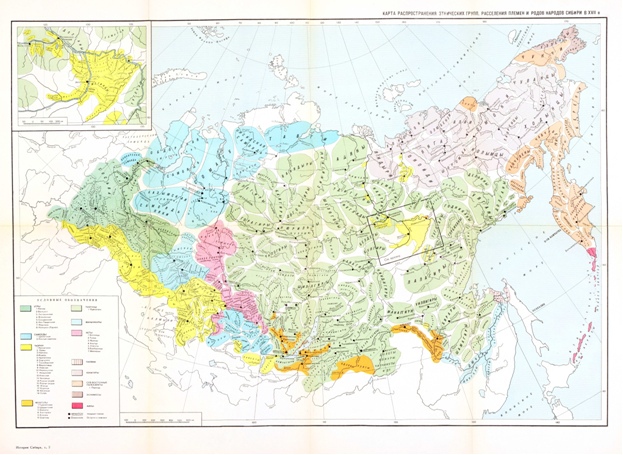

Since the 17th century, the ethnic and linguistic environments have significantly changed. If we consider the map of ethnic group distribution in the 17th century (Figure 1), drawn by Boris Dolgikh, we will see that by the 17th century, Yakuts had not yet occupied the present-day territories and were very far from Taymyr. So, one cannot surmise that the emergence of the Dolgan language could have started in its present-day area of distribution.

B.O.Dolgikh. Map of distribution of ethnic groups in the 17

th

century.

The Dolgan language is similar to Yakut in its main characteristics, and its grammatical system proves it is a typical Turkic language. Yet, the similarity might be smaller than meets the eye: even in those cases when Dolgan uses unquestionably Yakut forms, the rules of their use might be closer to the rules of use of a form in Evenki or Nganasan. Figuratively speaking, Dolgan is an Evenki language in Yakut clothing, which in Taymur gets worn in a Nganasan manner. We will show such a ‘reorganization’ of genuinely Turkic material after Evenki or Nganasan patterns later. This map was drawn by B.O. Dolgikh and published in his Origin of Dolgans. The map shows the distribution of Dolgans a hundred years ago and provides a picture of the factors impacting the development of Dolgan: areas with the then Evenki speakers who later started to speak Dolgan, and the vast area of Nganasan-Dolgan contacts (including the zones of common nomadic

migrations).

Dialect situation

There are no distinct dialects

Short history of studying the language.

Dolgan was for a long time considered to be a dialect of Yakut. Linguistically both languages are really close to each other. But, as Polish Dolgan expert Marek Stachowski justly points out, to define whether Dolgan is a separate language, it is important to take into account not only linguistic facts, but also the self-identification of people speaking the language. Dolgans are a very young but independent ethnos, and Dolgan is a separate language.

The first person to describe Dolgan was Elizaveta Ivanovna Ubryatova, the author of The Language of Norilsk Dolgans (1985). The Dolgan poet Ogdo Aksenova was an icon: she wrote the first literary works in Dolgan and in effect created the first ever variant of the Dolgan writing system. In the 1990s, Polish linguist Marek Stachowski published an academic dictionary of the Dolgan language and wrote and published several articles on Dolgan. In 2013, Eugenie Stapert (Netherlands) defended a dissertation on linguistic contacts in the history of the Dolgan language. In 2016-2019, Hamburg University researchers created the INEL Dolgan Corpus, and now Chris Däbritz is working on a new Dolgan Grammar built on the Corpus data.

In Japan, a Dolgan dictionary is being compiled by Professor Setsu Fujisiro, who is using in her work archive notes made by ethnographer Konstantin Mikhailovich Rychkov in the early 20th century.

Main linguistic information (phonetics, grammar, lexis)

Phonetics

Dolgan has a typically Turkic system of 8 monophthong vowels (which can be either long or short), with four more diphthongs. These monophthongs and diphthongs break into groups with different properties: front or back vowels, narrow or wide vowels, labialised or non-labialised vowels:

|

|

front

|

back

|

|

|

labialised

|

non-labialised

|

labialised

|

non-labialised

|

|

|

monophthongs

|

diphthongs

|

monophthongs

|

diphthongs

|

monophthongs

|

diphthongs

|

monophthongs

|

diphthongs

|

|

wide

|

ө [ö]

|

|

э [е]

|

|

о [o]

|

|

а [a]

|

|

|

narrow

|

ү [ü]

|

үө [üö]

|

и [i]

|

иэ [ie]

|

у [u]

|

уо [uo]

|

ы [y]

|

ыа [ya]

|

These oppositions are the basis of so-called vowel harmony: one word can only have either front or back vowels, for narrow vowels it is important whether the vowel is labialised or not. Vowel harmony can be seen with utmost clarity when suffixes are added: wide-vowel suffixes have two variants (with the front [e] and the back [a]), narrow-vowel suffixes have four variants (with the front labialised [ü/ IPA y], the front non-labialised [i], back labialised [u] and back non-labialised [y/IPA ɯ]. The suffix variant is chosen on the basis of the vowel of the preceding syllable. Lower we provide the forms of so-called “past tense” (which in Dolgan actually describes a situation close to completion or stopping) for four verbs:

a

haa

- ‘eat’ (back vowel in the stem)

die

- ‘talk’ (front vowel in the stem)

buol

- ‘become’ (back labialised vowel in the stem)

üt-

‘push’ (front labialised vowel in the stem).

The past tense indicator and the first-person plural indicator contain narrow vowels, so they have four variants each, third-person plural indicator contains a wide vowel, so it has two variants.

FirstPperson Plural:

|

Stem

|

Past Tense indicator

|

1 person Plural indicator

|

|

ahaa-

|

-ty

|

-byt

|

|

die-

|

-ti

|

-bit

|

|

buol-

|

-lu

|

-but

|

|

üt-

|

-t

ü

|

-b

üt

|

Third Person Plural:

|

Stem

|

Past Tense indicator

|

3 person Plural indicator

|

|

ahaa-

|

-ty

|

-lar

|

|

die-

|

-ti

|

-ler

|

|

buol-

|

-lu

|

-lar

|

|

üt-

|

-t

ü

|

-ler

|

Consonantal system of Dolgan

|

Labials

|

Dentals

|

Palatals

|

Velars/

pharyngeal

|

|

м [m]

|

н [n]

|

нь [n’]

|

ӈ [ŋ]

|

|

п [p]

|

т [t]

|

|

к [k]

|

|

б [b]

|

д [d]

|

дь [d’]

|

г [g]

|

|

|

с [s]

|

|

h [h]

|

|

|

|

ч [t͡ʃ]

|

|

|

|

й [j]

|

|

|

|

|

л [l]

|

|

|

|

|

р [r]

|

|

|

Morphology

From the morphological point of view, Dolgan (like the other Turkic countries) belongs to agglutinative languages. It means the following:

-

A great many grammatical meanings are conveyed within the word, with the help of suffixes (all the grammatical indicators in Turkic languages are suffixes);

-

all the Dolgan grammatical indicators are regular. Agglutinative languages do not have irregular unpredictable diversity of markers with the same meaning such as Russian в дом-е (v dom-e), в шкаф-у (v shkaf-u), в здани-и (v zdani-i). Even if there are several variants of the indicator, their choice is completely predictable. For instance, the Dolgan noun plural marker has 16 variants, but the variant chosen always complies with precise and simple rules: it follows the rules of vowel harmony, and it depends on the preceding consonant, for instance: ünküü (үнкүү) ‘dance’ ~ ünküü-ler (үнкүү-лэр) ‘dances’, tyl (тыл) ‘word’ ~ tyl-lar (тыл-лар) ‘words’, mas (мас) ‘tree’ ~ mas-tar (мас-тар) ‘trees’, üör (үөр) ‘herd’ ~ üör-der (үөр-дэр) ‘herds’, aan (аан) ‘door’ ~ aan-nar (аан-нар) ‘doors’;

-

In Dolgan, as well as in any other agglutinative languages, there is a strong tendency to have a special indicator for every grammatical meaning: for instance, one single indicator in Russian can show both the case and the plurality: в нарт-ах (v nart-akh), while in Dolgan these two meanings will be conveyed through the use of two separate markers: hyyrga-lar-ga (hыырга-лар-га) ‘in the sleds’.

Lexis

We mentioned many times that Dolgan is unique because of its system being reconstructed and enriched by the influence of other languages, above all Evenki, Nganasan, and to a smaller degree, Enets. Linguistic contacts can be most easily traced by looking at the vocabulary of the language. As a rule, borrowed words can be classified by their meanings into different groups. It is all because words are not borrowed chaotically: as a rule, new loan words in a language denote new objects or new methods of economy (for instance, in the fields of deer herding or hunting). In linguistics such words are labeled as cultural lexis – these are the words, that can be borrowed while contacting with and getting to know a different type of traditional culture with borrowing certain of its elements.