Demographics

The total number of Vepsians, according to the 2020 All-Russian Population Census, is 4,687 people (2,066 men and 2,621 women).

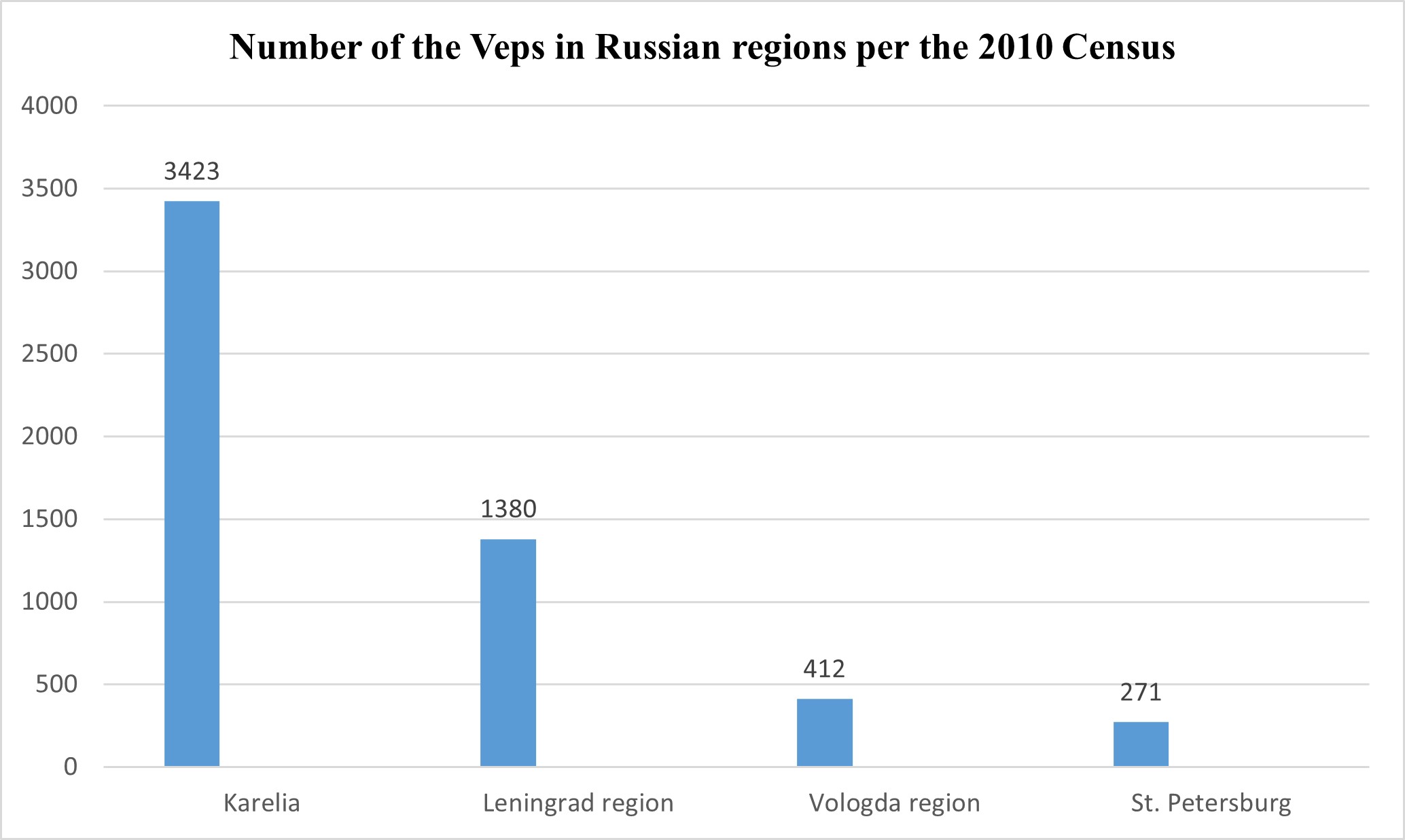

The 2010 census puts the number of the Veps at 5.936 persons: 3.423 (57.6%) in Karelia, 1.380 (23.2%) in the Leningrad region, 271 (4.6%) in St. Petersburg, and 412 (6.9%) in the Vologda region.

In the 20

th

century, the Veps were predominantly rural. However, the 2002 census for the first time showed higher numbers of urban population (56.1 %). The indicator did not change in 2010 (56.4%), although the situation varies in different regions of the Veps’ traditional residence.

Recently, the number of urban Veps in the Leningrad region has never been greater than a quarter of the region’s entire Veps population. They mostly lived in district centers and urban-type settlements close to Veps villages. The St. Petersburg Veps numbered 318 in 2002 and 271 in 2010. In Karelia, the urban Veps population has been larger than the rural Veps population since the 1970s, whereas in 2002 and 2010, nearly two-thirds of the republic’s Veps population lived in cities.

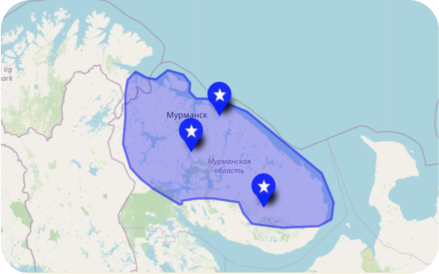

At the moment, Petrozavodsk has been home to the largest Veps population in Russia (about 2.000 people). The Vologda region has the smallest share of urban Veps population (12.6%). In 2010, 450 Veps lived outside these regions that had historically been the Veps’ homeland; of them, most lived in the Murmansk and Kemerovo regions (82 and 46 persons respectively). Other 55 regions have between a few and two dozen Veps. Overall, women dominate the Veps population, and that imbalance is particularly evident among the urban Veps of Karelia.

In 2002-2010, the number of the Veps dropped by 28%, equally among the rural and urban Veps. The Vologda region Veps showed the smallest drop of 3.3%. The Veps’ numbers are falling fast beyond their traditional homeland, too.

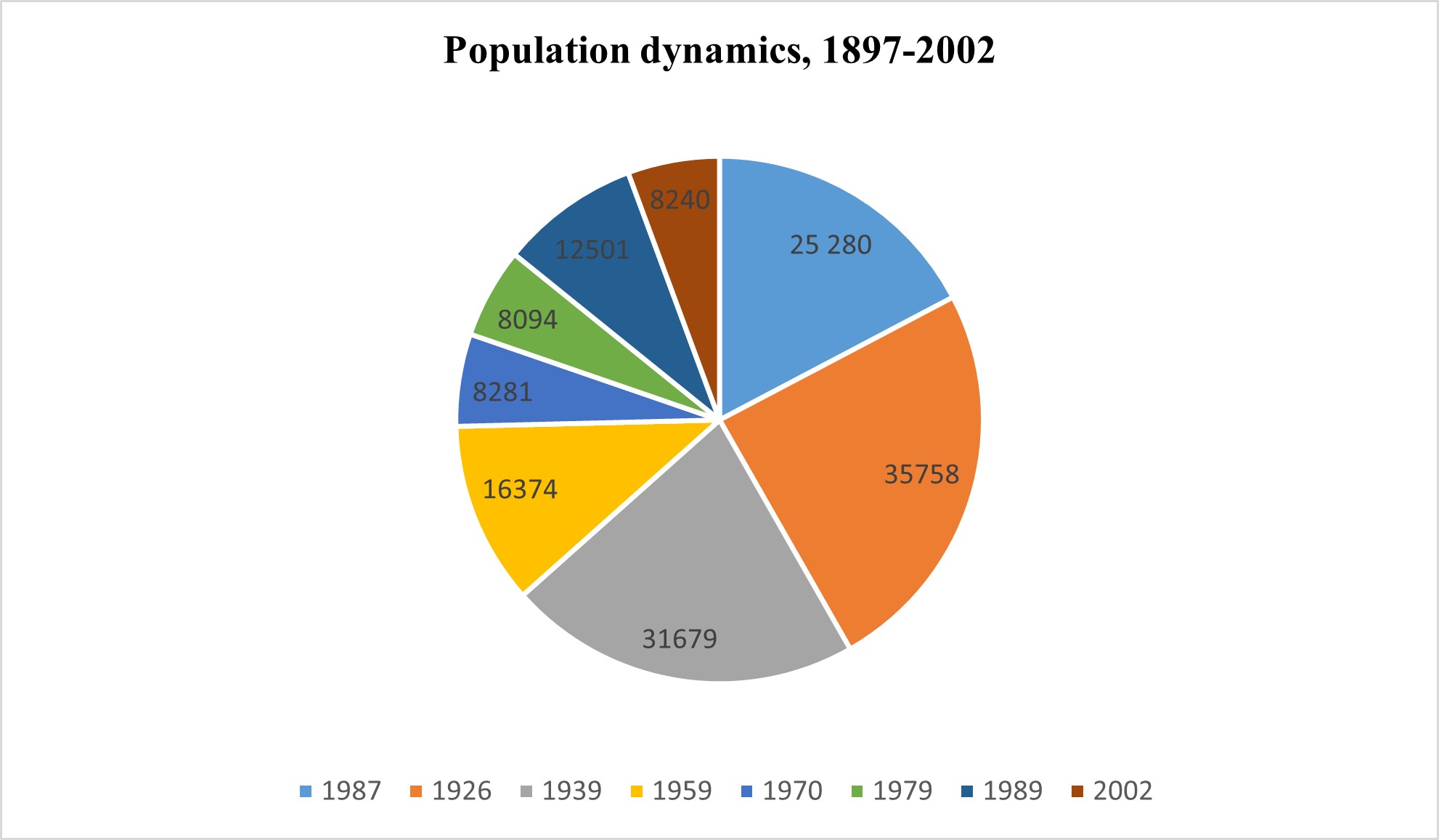

Numbers of the Veps peaked in 1926 at 32.800 persons. At that time, three quarters of the Veps population lived in the Leningrad region, and a quarter lived in Karelia. The Veps found themselves in the Vologda region in September 1937 when part of the Leningrad region’s territory was transferred over from the Leningrad region.

The ratios of different Veps groups changed as well. Up until the 1930s, three-quarters of the Veps lived within territories that are currently part of the Leningrad and Vologda regions, today, the ratio is different: three-quarters of the Veps live in Karelia.

As of today, the Veps population has significantly aged, which is typical for actively assimilated ethnic communities. The share of the elderly among the Veps of Karelia is 35.1 % of the entire Veps population (21.7 % for men and 44.1 % for women). Their median age is 47.8 years (the median age of Karelia’s Russians is 34.0 years). The Veps of the Leningrad region demonstrated an even more drastic aging: 55.9 % of the Veps (40.4 % of men and 66.0 % of women) are of retirement age, and their median age is 62.9 years (Russians’ median age is 39.4 years).

In 2000, the Veps were granted the status of an indigenous small-numbered people of the Russian Federation; in 2006, the Veps were put on the list of indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Russian Far East. The list of the Veps’ traditional places of residence includes 11 rural settlements: Shokshinskoe, Sheltozerskoe, Ryboretskoe in Karelia; Vinnitskoe, Voznesenskoe, Alekhovshchinskoe, Pashozerskoe, Radogoshchinskoe in the Leningrad region; Timoshinskoe, Pyazhozerskoe, Oshtinskoe in the Vologda region. They are home to about 2,500 Veps.

Today, the Veps as an ethnic community are at the depopulation stage. This process was launched in the late 1930s with the authorities’ steps that weakened the Veps’ inter-ethnic consolidation. A single ethnic territory was divided between different regions and different districts within each region. As a result, several Veps ethnic territorial units were dissolved, and the Veps writing system was abolished; the Veps language was banned from public and cultural areas, and the burgeoning Veps intelligentsia suffered repressions.

Mass migration of the Veps (mostly younger generations) beyond their ethnic territory with no institutions in place to support their ethnic identity among a different ethnicity resulted in a rapid linguistic and ethnic assimilation of Veps migrants and widespread interethnic marriages. The decision made in the Leningrad and Vologda regions to exclude the Veps from the official statistics in the 1970 and 1979 censuses and record them as Russians in their passports and other official documents further advanced assimilation.

The young generation leaving Veps villages resulted, in turn, in the drastic aging of the remaining rural Veps population and undermined the demographic potential for the further reproduction of the Veps population. Since the 1980s, the numbers of the Veps have been falling both due to ethnic assimilation, and also to natural population decline. An upsurge in ethnic self-awareness at the turn of the 1980s-1990s helped maintain Veps numbers for a while, but the negative consequences of socioeconomic transformations of the early 1990s dealt a particularly painful blow to the rural population and invalidated the results of the “ethnic resurgence.”

In 1989-2010, the demographic situation stagnated in Karelia but continued to deteriorate in the Leningrad region. Here, the Veps population declines at a higher rate than in Karelia. In the Vologda region, the situation is stabilizing, but its population is too small to improve the situation. The Veps urban population in Karelia resides virtually entirely in Petrozavodsk and cultural and educational policies and public organizations’ activities maintain its demographic stability. Enforcing the legislation intended to advance the socioeconomic development of the Veps’ traditional homelands could serve as an important step in preserving the Veps rural population; such a step has been envisioned for preserving small-numbered indigenous peoples of the North, Siberia, and the Russian Far East.