|

|

Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology, Russian Academy of Sciences

Maria Pupynina

|

Koryak (Chavchuven)

I.

Sociolinguistic Data

1. Existing alternative names for language and ethnic group

In pre-Soviet times, sedentary inhabitants of the Penzhinskaya Bay and nomadic reindeer herders in the northern part of the Kamchatka Peninsula were commonly referred to as Koryaks. Inhabitants of the shores of Kamchatka were called Lyutors or Alyutors, and their language had a certain similarity to that of Koryaks. In the 1930s, all these groups (sedentary Koryaks, reindeer herders, and Alyutors) were referred to as Nymylans in accordance with the self-designation of Alyutors and certain other sedentary groups, whereas their language was called Nymylan or Koryak. At the time, it was believed that the Koryak language was divided into 8 dialects, including Alyutor, some of which had very peculiar features. In the post-war period, Nymylans were not mentioned anymore either in official documents, or in everyday use, only the Koryak name was used, and all their languages and dialects were generally referred to as the Koryak language. In the 1970s, following the expedition of Moscow linguists A. Kibrik, I. Muravieva, and S. Kodzasov, the Alyutor dialect of the Koryak language was recognized as a separate language. However, the status and number of other dialects still remain controversial.

The literary Koryak language was based on the parlance traditionally used by Chavchuven nomads. Today, Koryak is sometimes also referred to as Chavchuven (cf. article in the Great Russian Encyclopedia). The Koryak-Chavchuven people call their language

чав’чывэн йилыйил

,

чав’чываелыел

[Chavchuven language] (

йилйыл

‘language’ +

чав’чывэн, чав’чыва- ‘

Chavchuven’).

Our description of the sociolinguistic situation concerns mainly the Chavchuven dialect of the Koryak language and/or the Koryak language in its written form. The fact that the Chavchuven dialect was chosen as a basis for written language had fundamentally affected its status and prevalence compared to the pre-written period. Any references to other dialects are specifically indicated.

II. General Characteristics

2.1. Total number of speakers and their ethnic group

According to the 2010 All-Russian Population Census, 1 665 people indicated that they spoke Koryak. Native speakers of Alyutor also identified themselves as speaking Koryak, since most of them are used to this official scientific interpretation. Yukari Nagayama, a Japanese field researcher, calculated that in 2015 around 200 people spoke the actual Alyutor language, as well as Palan and Karagin dialects of Koryak that greatly resemble it. They were all residents of the Kamchatka Territory. Therefore, there are about 1 450 people fluent in Koryak (the main Chavchuven dialect, as well as Pareni, Kamensk, and Apukin dialects that share some similarities with it). Most likely, this list includes both fluent users and those who only understand some phrases and/or can say a few words.

Based on the 2010 Census, there are 7 953 ethnic Koryaks in Russia, including traditional reindeer herders (Chavchuvens) and sedentary people (Nymylans).

2.2. Threat of extinction and age of native speakers

Koryak is threatened with extinction, since the middle and younger generations do not actively use it. At best, they are passive speakers, they can understand it, but do not speak it.

The language shift (i.e. from Chavchunen to Russian) in Kamchatka happened as follows. Today, Russian is the main mode of communication in local towns and villages. All Koryak native speakers are fluent in Russian. They only use national language from time to time, with Russian being the dominant medium of communication. However, people aged over 50 remember that they went to school without any knowledge of Russian. Growing up, representatives of the older and middle generation (1940s–1970s) heard only national language at home, but they all went to Russian boarding schools, where their native language was not taught. In the middle of the 20

th

century, following the mass arrival of Russian male population in traditional Kamchatka villages (brought here for construction and development of the collective farming system), mixed marriages started to prevail, In such families, Russian became dominant even in interpersonal communication. The capacity to preserve the language that a person used in childhood depends on the person’s abilities and the circumstances of his/her individual life history. The language is well preserved in national families, where both husband and wife are fluent in their native ethnic language. Still, some native speakers of Koryak keep it in their memory, even after having spent some time «on the mainland» in the Russian-speaking environment, and are able to restore their language proficiency to its previous level upon return. Moreover, they remember not only everyday expressions, but even obsolete national vocabulary, they compose stories in Koryak with ease. People aged over 50 have a good command of the language. The younger generation (born after 1980) consists of passive users of the national language, they understand it but prefer speaking Russian.

Presently, the attitude towards Koryak is overwhelmingly positive. Language is a tool for ethnic self-identification. The older generation sincerely regrets that it was unable to pass it on to their children and grandchildren. According to Koryaks and Chavcuvens of a certain age, they are hindered, above all, by the lack of skills in recording their native language. Their inability to record memories, fairy tales, stories in their mother tongue renders impossible the narrative self-expression of ethos, therefore, the probability of transmission of Koryak and Alyutor linguistic heritage through writing and reading is very low.

2.3. Use in various spheres of communication

Koryak is used in communications between families and friends among people aged over 50. Whenever younger people are involved in the conversation, it is carried out in Russian, although older people often utter remarks in national language that young people understand, but answer in Russian.

Chavchuven dialects are sometimes used as a secret language that allows people to discretely exchange information in a Russian-speaking group.

Whenever there is a person capable and willing to teach Koryak in a nursery school, the local administration of preschool educational institution does everything in its power to make it possible. We know that there are lessons of national language in the nursery schools in Manila, Penzhinsky district, and Palana, Tigil district. It is highly likely that this initiative is also supported in other towns and villages of the former Koryak National District.

Valentina Dedyk, a highly enthusiastic teacher-methodologist, has been actively compiling textbooks and methodological aids for Koryak. She was in charge of publication of a series of textbooks, ABCs, manuals for teachers, the development of a state-supported training program. As far as we know, Koryak lessons became compulsory in all primary schools of the former Koryak National District since 2022. In middle and high schools, it is left to the discretion of school administration, when competent teachers are available. There is an annual selection of best essays written in the national language.

Students of Preschool Education and Teacher of Primary School Departments of Palana College, a secondary technical school, can obtain an additional diploma as teacher of national (Koryak) language. For many years now, the Palana College has the Methodical Department with teachers of Koryak, Ewenki, and Itelmens languages. The Institute of Peoples of the North (within the Herzen State Pedagogical University in St. Petersburg) also prepares Koryak teachers.

The Koryak National District newspaper

Narodovlastie

in Palana occasionally publishes small articles in Koryak. Unfortunately, there are no online versions of this editions.

There are small news articles in Koryak online:

Новости Камчатки на корякском языке за 22.10.2020 г. (poluostrov-kamchatka.ru)

[News of Kamchatka in Koryak as of October 22, 2020]

Эчгыпо Камчаткакенав' чав'чываеличг'энаӈ 29.06.2020 г. (fareastvip.ru)

On weekdays, there are daily morning editions of radio news programs in Koryak in the Kamchatka region (prepared by Svetlana Moiseeva, maiden name Tynanto). Some broadcasts are simple translations of Russian news, but they often include interviews with Koryak speakers. Radio broadcasts are not available online.

The local TV-station broadcasts newscasts in Koryak 3 times a week. The duration of each program is 20 minutes. Its Chavchuven host is Tatyana Nutelhut. Unfortunately, few of the episodes are available online, so one can only watch it in Kamchatka.

The increase in ethno tourism in Kamchatka contributed to the popularity of folk dance companies encompassing the representatives of all indigenous ethnic groups of the peninsula: Itelmens, Koryaks (Chavchuvens) and Koryaks (Nymynlans or Alyutors), Evens. Stage performances occasionally include songs or lines in Koryak and Alyutor.

Oral tradition still contributes to the preservation of fairy tales, historical legends in Chavchuven. Based on the results of expeditionary studies, the Kamchatka Folk Art Center publishes an annual edition of folklore texts in Koryak and Alyutor. All editions are available online on the Center’s official website: https://www.kamcnt.ru/publications/.

2.3. Information about written language

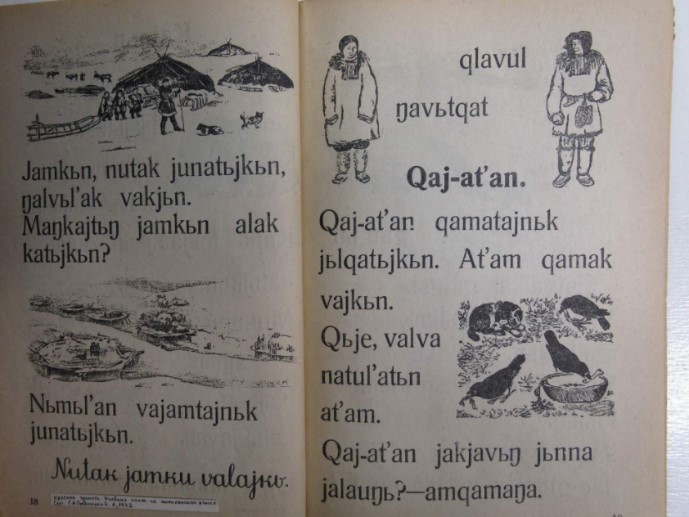

In 1932, a group of scientists from Leningrad led by V. Bogoraz developed a Latin-based Koryak alphabet. The first book in Koryak, an ABC for students called

Jissa-kalikal

[Red Book], was published in 1932.

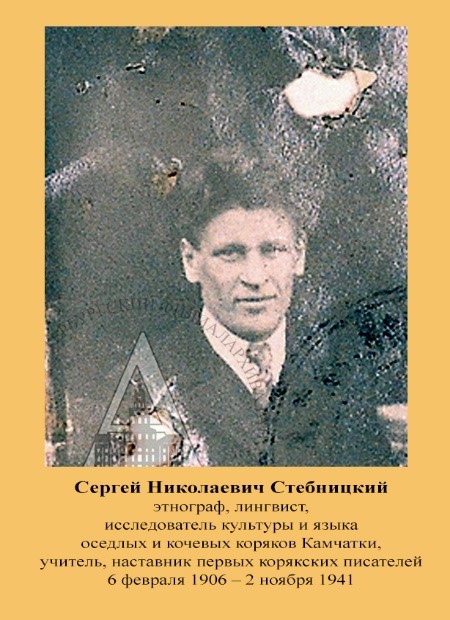

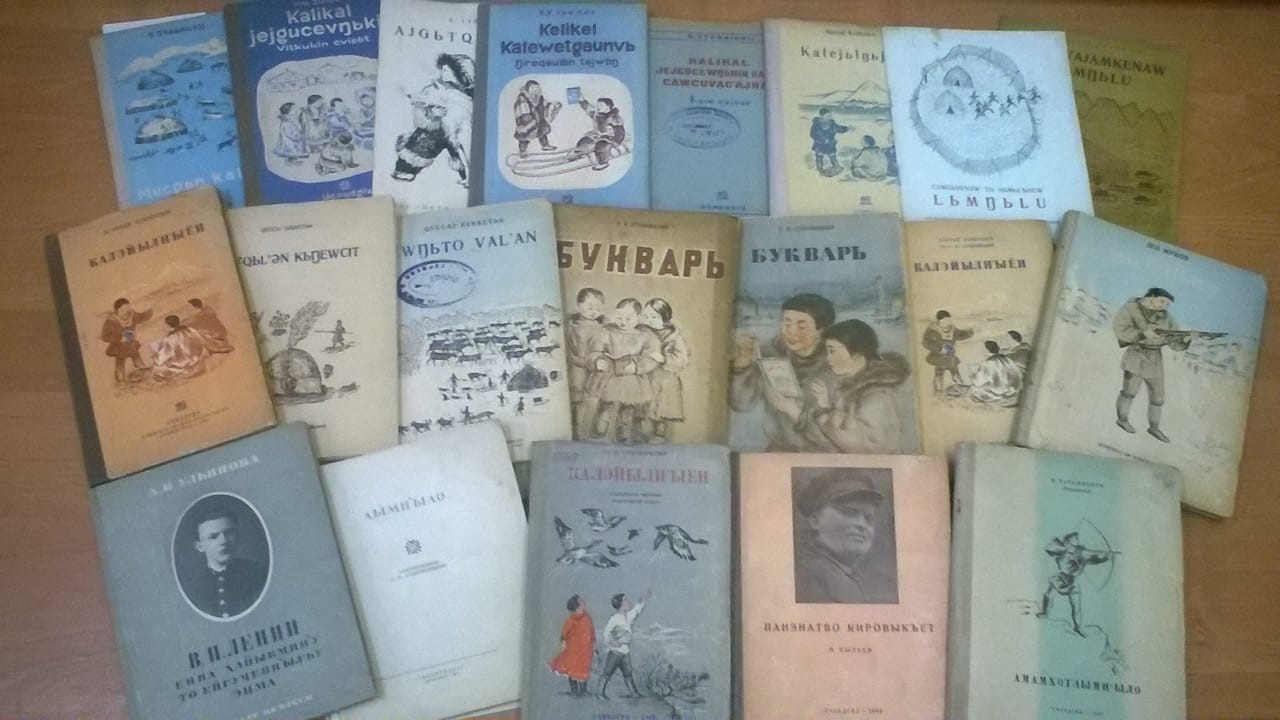

In 1933, the originally adopted alphabet was somewhat modified. The year of 1934 saw the beginning of active publication of books in Koryak. Within a very short time, Sergey Stebnitsky, a linguist from Leningrad, contributed to the publication of various translated texts, samples of Koryak folklore, original stories in Koryak. Not only did he personally translate fiction and political texts from Russian into Koryak, but he also encouraged students from the Institute of Peoples of the North, native Koryaks, to create original texts in their native language. Over the period from 1932 to 1940, over fifty books in Koryak with a total circulation of more than 73 000 copies were prepared with his direct involvement. Even though the number of Koryaks in the 1926 Census totaled 7 434 people.

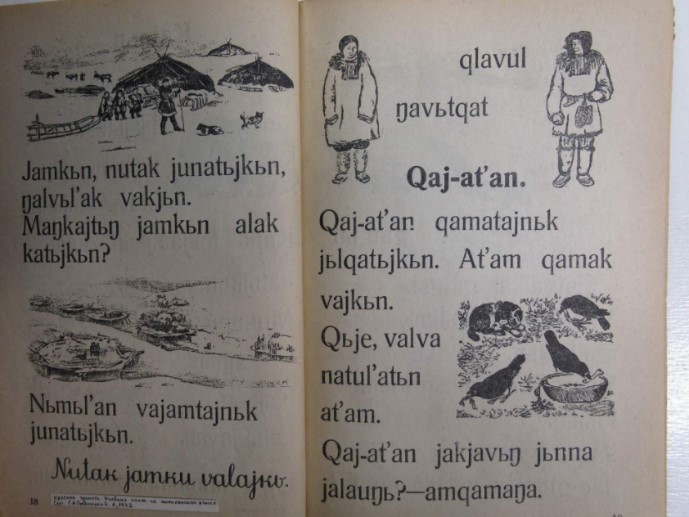

A page of the first edition in Koryak. «Jissa-kalikal» [Red Book]. L., 1932.

However, the books published in Leningrad weren’t delivered to Kamchatka schools and libraries. By way of proof, we shall quote the 1941 edition of

Koryaksky Bolshevik

, a Kamchatka newspaper. There is an article containing reference to the Nymylan (Koryak)-Russian Dictionary published in Leningrad in 1939. The end of the article is particularly noteworthy: “…There were printed 2 000 copies of the dictionary. It is such a pity that the region still has not received dictionaries. It only got 2 copies”. (Нымыланско-русский словарь [Nymylan-Russian Dictionary].

Корякский большевик (

1941, July 7).

Later, Koryak writer Vladimir Koyanto (Kosygin) wrote that enormous quantities of books had been stored for decades in Kamchatka warehouses. He ended up in one of those warehouses in the early 1960s: “A warehouse full of half-rotten ABCs in native languages, first books written by Koryak writers delivered by steamboat to the district center once upon a time before the war, quietly wasted away from its uselessness...” (Koyanto V. Что в имени твоём, Кецай? [What’s in a name, Kesai?] In Koyanto, V.

Тумми: Проза.

[Tummi: Prose]. Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, 2006. P. 49.)

From 1934 to 1937, a Latin-based alphabet was used to write down and publish texts in Koryak. The first textbooks and fiction in Koryak were published in Latin characters.

Both the first students of schools for eradication of illiteracy in northern villages of Kamchatka and the first Koryak students of the Institute of Peoples of the North learned to write using a Latin-based script. In 1934-1935, Koryak students led by S. Stebnitsky published a national page, supplement to the

INSovets

newspaper, where they ran their original stories in native language.

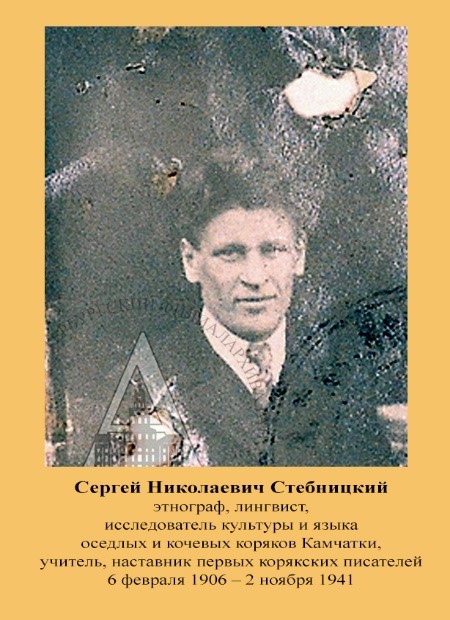

S. Stebnitsky, creator of the Koryak writing system

It should be noted that the Latin-based alphabet, used in Koryak from 1934 to 1937, was very convenient, it reflected the main phonological particularities of the Koryak language. In this graphical system, the softness of consonants [n

j

], [l

j

], [t

j

], including those before non-full vowels, was indicated with subscripts

ņ

,

ļ, ţ

; the nasal guttural, with letter

ŋ

; the uvular stop, with

q

. There were two ways of recording the indeterminate vowel [ә]: either

ь

or

ә

, depending on the vowel’s position within the word.

At the end of 1937 – beginning of 1938, a new alphabet based on Cyrillic characters was developed for Koryak language. This new Cyrillic-script alphabet was introduced for Koryaks, as well as all other peoples of the USSR with a recent writing tradition, for political reasons, but it turned out to be much less convenient for transmitting phonetic peculiarities of the Koryak language. The new orthography used no subscripts at all, therefore, it was impossible to indicate the softness of a consonant before an indeterminate vowel, which was now transcribed as the letter

ы;

the labial consonant [w], as well as the labiodental [v], as

в;

the uvular [q], as

х;

and the velar nasal consonant [ŋ], as a graphic combination of a letter with an apostrophe

н’

.

The established Koryak writing system was annihilated. Numerous printed Latin-based Koryak books were banned and destroyed. Today, the copies of pre-war books in Koryak in the collections of Kamchatka libraries bear library stamps from the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic. Following the relaxation in political sphere, the surviving copies of Koryak books were sent to Kamchatka by Ukrainian librarians. These books sent from Ukraine remain the most valuable exhibits of Kamchatka library collections to this day.

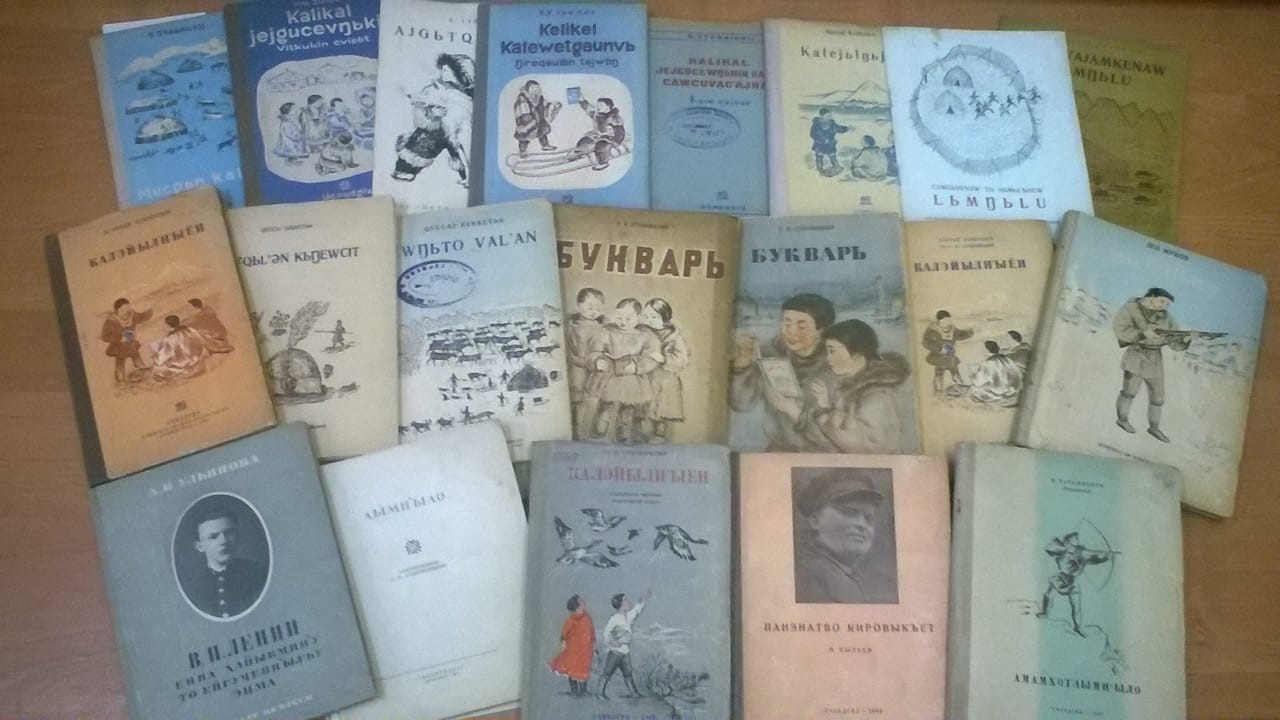

Books in Koryak that were published in the 1930s with the direct involvement of S. Stebnitsky

The system of Cyrillic-based recording of Koryak texts, developed in December 1937, was not widely adopted. In the 1950s, one begins to observe graphic and spelling inconsistencies in Koryak publications. These changes in orthography were mostly of a spontaneous nature and resulted from personal positions of authors and editors of rare small books in Koryak.

The modern Koryak alphabet was approved in 1960, following the publication of the Koryak-Russian dictionary compiled by T. Moll. Additional characters were introduced to the new alphabet to designate specific Koryak sounds:

ӄ

[q],

ӈ

[ŋ],

в’

[w],

г’

[ʕ]. The version of the Koryak alphabet adopted in 1960 is still considered to be a standard.

The following letters of the Koryak alphabet are used to transcribe the original Chavchuven words: a [a], в [v], в’ [w], г [ɣ], г’ [ʕ], е [е], [je], ё [o], [jo], и [i], й [j], к [k], ӄ [q], л [l], м [m], н [n], ӈ [ŋ], о [o], п [p], у [u], ч [č], ъ, ы [ә], э [e], ю [u], [ju], я [a], [ja]. The following letters were introduced to transcribe loanwords:

б, д, ж, з, р, c, ф, х, ц, ш, щ

.

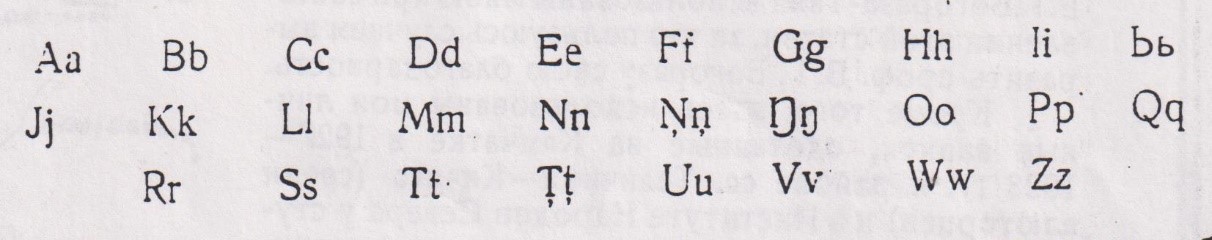

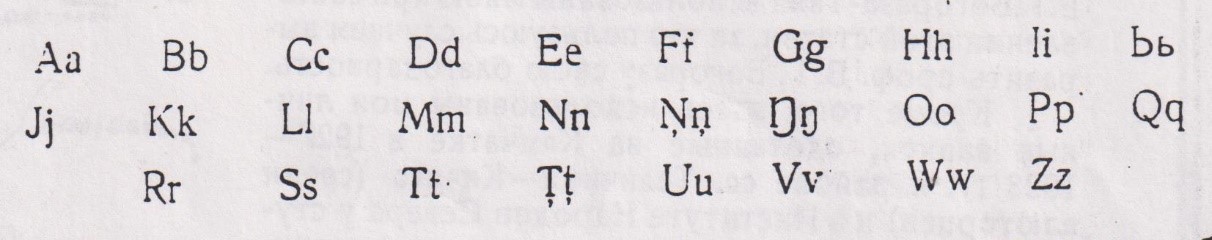

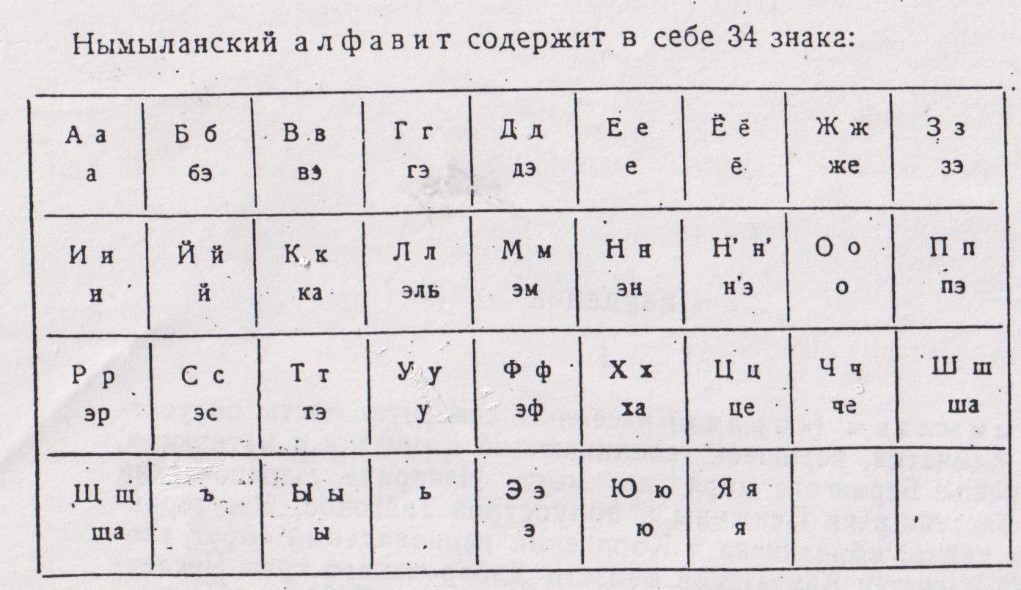

Latin-based alphabet of Nymylan (Koryak), valid from 1934 to 1937. It was published in Stebnitsky, S. Нымыланский (корякский) язык [Nymylan (Koryak) language].

In Языки и письменность палеоазиатских народов [Languages and writing system of Paleosiberian people]. Part III. M.; L., 1935.

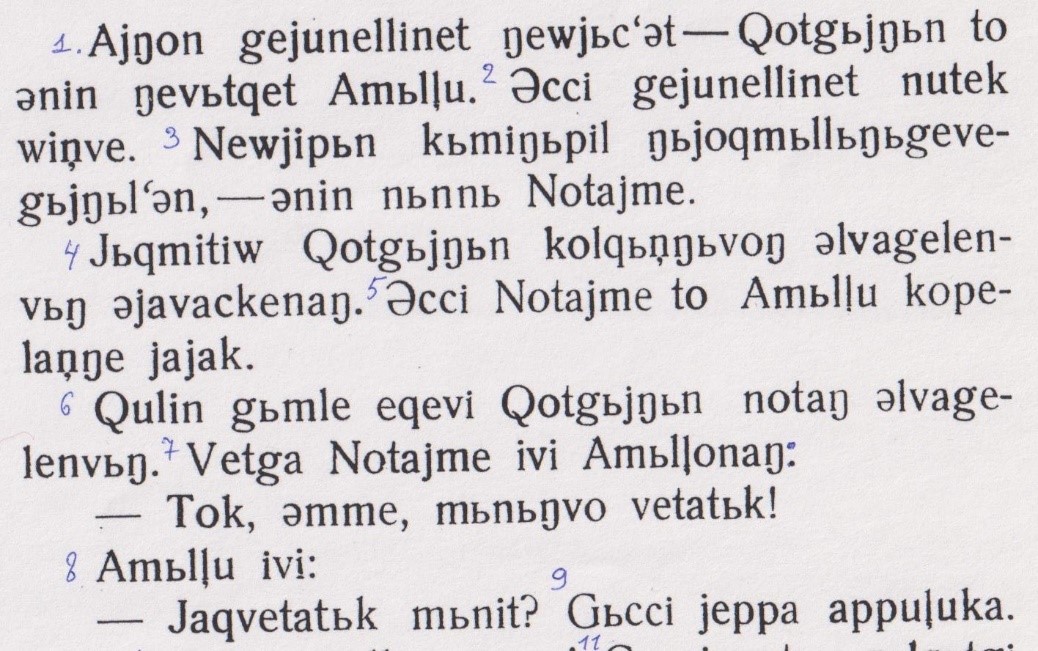

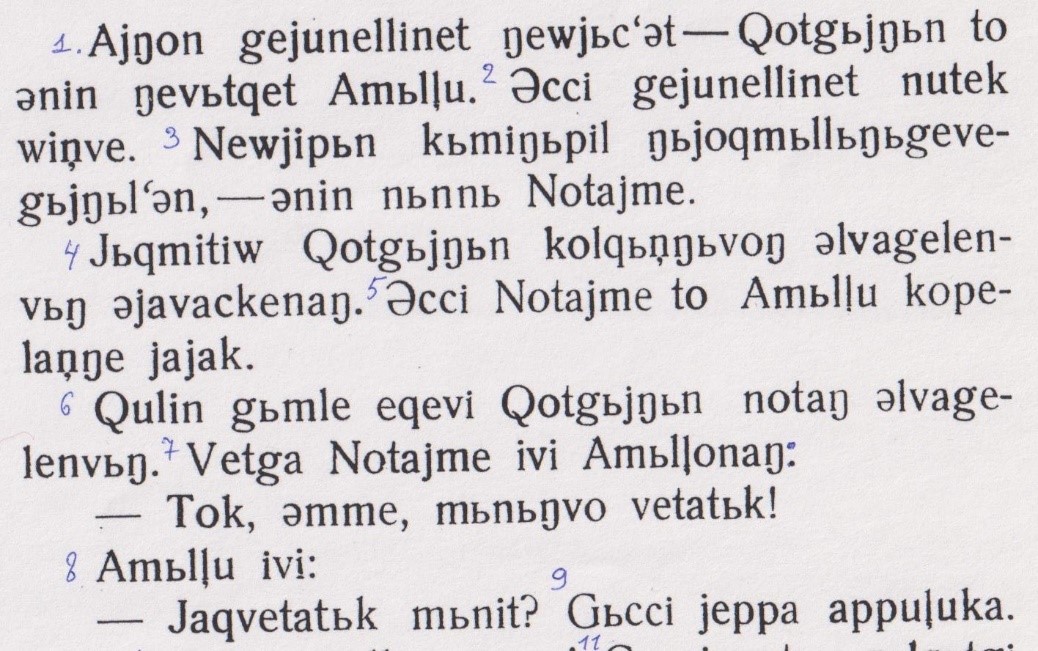

Sample of a Koryak text recorded with the Latin-based alphabet valid from 1934 to 1937.

The beginning of a historical novel Нотаймэ by Lev Zhukov published in 1937.

Zhukov, L. Нотаймэ: исторический рассказ на нымыланском (корякском) языке [Notajme: a historical novel in the Nymylan (Koryak) language]. M.; L., 1937.

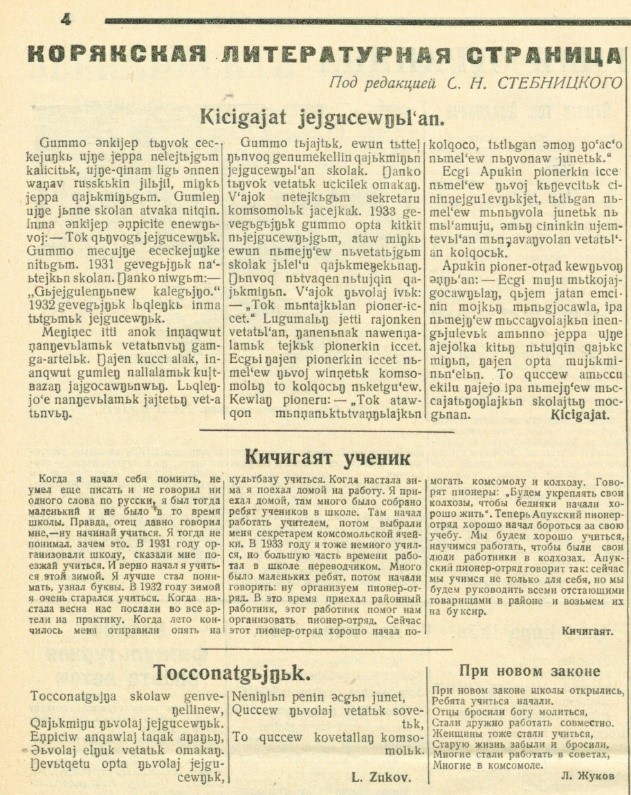

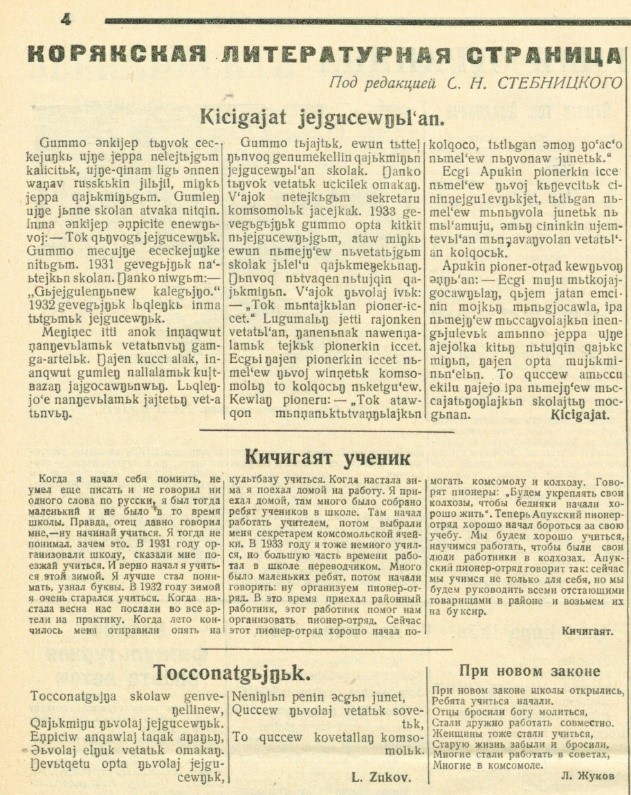

National Koryak page in the INSovets newspaper (Leningrad) of 15/06/1935

Unlike many other languages with a recent writing tradition that tended to go through a variety of graphic systems during the second half of the 20

th

century, the graphics of the Koryak language was adopted in 1960 and remained unchanged for 60 years. It would seem that the presence of a codified graphic system throughout this time would have facilitated the development of writing. But it was quite the opposite. Koryak was excluded from the school curriculum in 1953. The generation of Koryak Chavchuvans born between 1947 and 1973 did not master the skills of writing in their mother tongue. It was only in 1979 that Koryak was integrated into the school curriculum of the Koryak Autonomous District. Between 1961 and 1981, the publication of books in Koryak was virtually discontinued. The twenty-year gap in publishing activities prevented the written Koryak language from asserting itself and becoming truly relevant for the indigenous population of Kamchatka. Reading in Koryak requires a targeted training and a development of skills that do not correspond to those of reading in Russian. Some Koryak Chavchuvens create their own writing systems, compile their own handwritten dictionaries, while completely rejecting the official script as something wrong and incomprehensible.

In the meantime, teachers and methodologists of Koryak language, such as V. Dedyk, O. Bolotayeva, G. Kharyutkina, E. Pronina, as well as staff members of the Kamchatka Folk Art Center M. Belyaeva and A. Sorokin are working hard to publish Koryak school textbooks and teaching aids, archive materials. The publications of Koryak folkore texts prepared by the staff members of the Kamchatka Folk Art Center are available online:

www.kamcnt.ru

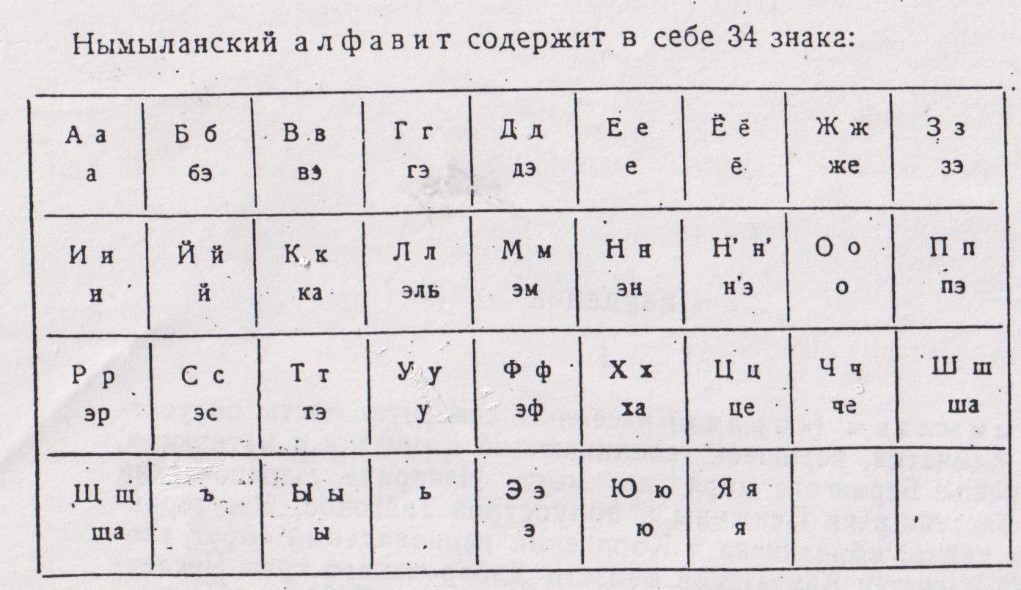

Cyrillic-based alphabet of Koryak valid from 1938 to the early 1950s.

It was published in: Korsakov, G. Самоучитель нымыланского (корякского) языка [Self-study Nymylan (Koryak) book]. L., 1940.

III. Geographic characteristics

3.1. S

ubjects of the Russian Federation with compact residence of native speakers

The Koryak native speakers live mainly on the lands of Kamchatka Krai that used to belong to the Koryak Autonomous Okrug (now non-existant). It includes the following districts: Penzhynsky, Olyutorsky, Tigilsky. Koryaks (Chavchuvens) also live in the Severo-Evensky District of Magadan Oblast.

3.2.

Total number of localities

There are 17 localities in Kamchatka Krai where people speak Koryak, and three in Magadan Oblast.

IV. Historical dynamics

It is extremely difficult to follow the dynamics of population speaking Koryak, since in all Censuses they were counted together with the speakers of Alyutor languages/dialects. However, the available data show the decline in numbers of both Chachuvens and Nymylans:

|

Census year

|

Indicated proficiency in Koryak/Alyutor

|

|

1926

|

7114

|

|

1959

|

5702

|

|

1970

|

6072

|

|

1979

|

5796

|

|

1989

|

5340

|

|

2002

|

3019

|

|

2010

|

2275

|

|

2020

|

Koryak 2633

|